Today marks the 75th anniversary of the opening of Kleinhans Music Hall in Buffalo, New York.

Home of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, Kleinhans is considered one of the world’s most acoustically perfect concert halls. It’s also one of Buffalo’s most significant architectural landmarks. Located in a leafy residential neighborhood just north of the city’s downtown, it anchors majestic Symphony Circle, part of Frederick Law Olmsted’s extensive parkway system which runs throughout the city. The Main Auditorium, featuring rich primavera flexwood walls and striking recessed lighting, has a seating capacity of around 2,800. A smaller multi-purpose hall seats 800. The lobby is a smoothly curving 40-by-185 foot Winona travertine arc.

The history of Kleinhans is a story of community-minded public investment. In the 1930s, Edward and Mary Seaton Kleinhans, who made their fortune from a high-end men’s clothing store which opened in Buffalo in 1893, specified that their estate be used “to erect a suitable music hall…for the use, enjoyment and benefit of the people of the City of Buffalo.” Additional funding came from the Works Progress Administration. The Buffalo Philharmonic and conductor Franco Autori performed the opening concert on October 12, 1940.

Kleinhans’ sleek, timeless design was created by Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen and his son, Eero Saarinen (who went on to design the iconic Gateway Arch in Saint Louis and the TWA Terminal at JFK Airport, along with some of the twentieth century’s most enduring furniture). Buffalo architects F.J. and William Kidd were also involved. Eliel Saarinen’s objective was to create “an architectural atmosphere…so as to tune the performers and the public alike into a proper mood of performance and receptiveness, respectively.”

Megan Prokes, a member of the Buffalo Philharmonic first violin section, shares a uniquely personal perspective on what it’s like to go to work at Kleinhans Music Hall:

Kleinhans Music Hall has always been an important part of my life in music. My parents moved to Buffalo not long before I was born, my father having acquired a job with the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra. Both of my parents are professional musicians, so it was only natural that as my younger sister and I grew up, we spent a lot of time at Kleinhans. My earliest memories of the hall are snapshots; the cacophony of instrumentalists warming up onstage before tuning, the broad staircases up to the balcony, the seemingly endless tunnels backstage and downstairs that lead to the music library, the musician locker areas, and out into the lobby through almost-hidden doors. Though it may sound strange, my most vivid and longest-held memory of Kleinhans is the scent of it, which has never changed. Familiar and comforting, I’d know blindfolded exactly where I was within a few seconds of entering the building.

When I think back on my childhood and early adulthood in Buffalo, and about my progress as a violinist, I see it mirrored in my relationship with Kleinhans. When I was little my mother would take my sister and me to the Discovery Concert series and I would look for my father, watch him as he came onstage. As I got older and more serious about music and the violin, I began to attend Classics concerts. I would sit impatiently, waiting for soloists like Itzhak Perlman, Yo-Yo Ma, Gil Shaham and many others to take the stage and teach me about passion, technique, dedication, and artistry. Backstage at every age, I would look forward to saying hello to all of my parents’ friends, my heroes, those who had taken their love of music and their instrument and made it their life. They always inquired after what I was working on, making me feel like a part of their world.Now, as an adult and a three-season member of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra myself, I look forward to working and performing in Kleinhans every day. The acoustics are everything that everyone says; rich, warm, well-balanced. While some say there’s no such thing as a “best seat in the house”, my favorite place to sit is front and center of the balcony. However, it is the entirety of what Kleinhans means to me, the representation of music and family, that makes it so special. My passion has become my lifestyle, my heroes have become my colleagues, and Kleinhans has become my second home.

BPO History Through Recordings

The 75th anniversary of Kleinhans Music Hall provides a great opportunity to celebrate the rich musical tradition of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra and to consider the ways an orchestra’s sound and style of playing are shaped by its hall. From the beginning, new innovative programming seems to have been one of the orchestra’s hallmarks.

Here is the orchestra’s first recording, made in 1946 at a newly-opened Kleinhans. In this excerpt, William Steinberg conducts Shostakovich’s Symphony 7 “Leningrad,” which at that time was a five-year-old work. Steinberg served as the BPO’s music director between 1945 and 1952:

Austrian conductor and violinist Josef Krips was music director between 1954 and 1963. In this live concert performance at Kleinhans on November 19, 1957, Krips leads the BPO in Mahler’s First Symphony:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PTHbhQLgTpE

American composer, pianist, and conductor Lukas Foss brought new, highly adventurous music to the Kleinhans stage during his tenure as music director between 1963 and 1971. His first concert with the BPO included the orchestra’s debut performance of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Buffalo audiences were less than enthusiastic about Foss’ avant-garde programming, but he continued to push the envelop, saying, “To take refuge in the past is to play safe. Safety lurks wherever we turn. Show me dangerous music.”

Foss’ GEOD, written in 1969, features amplification and strange collage techniques which might remind you of sounds The Beatles were creating around the same time. The music floats through a mysterious, gradually changing landscape. As fragments of folk songs emerge and disappear, the spirit of Charles Ives seems to be lurking in the background.

Michael Tilson Thomas, music director between 1971 and 1979, continued Buffalo’s tradition of innovative programming. Here is Sun Treader by American composer Carl Ruggles (1876-1971):

Current Music Director JoAnn Falletta has extended the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra’s discography with numerous releases on the Naxos label. One of her most interesting projects has lifted the music of Marcel Tyberg, a composer who perished at Auschwitz, out of obscurity. Falletta tells the amazing story of how Tyberg’s scores survived and ended up in Buffalo.

Here is Marcel Tyberg’s Symphony No. 3 in D minor:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find Buffalo Philharmonic recordings at iTunes, Naxos.

- Kleinhans Music Hall: A Study in Modern Sound by Denise Gail Prince

- Society of Architectural Historians Tour

[/unordered_list]

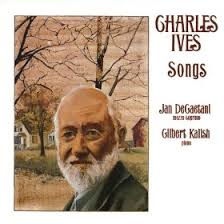

In the virtual isolation of early twentieth century New England, an organist and insurance salesman named Charles Ives (1874-1954) was imagining shocking and innovative new music. Ives created atmospheric collages of sound. He poured fragments of American folk songs and other material into a musical melting pot to create an exciting cacophony. Much of his music became widely known only decades later when other composers embraced similar techniques.

In the virtual isolation of early twentieth century New England, an organist and insurance salesman named Charles Ives (1874-1954) was imagining shocking and innovative new music. Ives created atmospheric collages of sound. He poured fragments of American folk songs and other material into a musical melting pot to create an exciting cacophony. Much of his music became widely known only decades later when other composers embraced similar techniques.