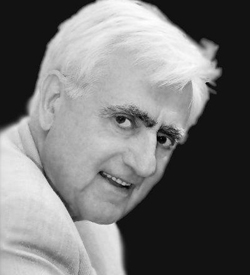

Korean-American pianist Hugh Sung can be described as a musical Renaissance man. A graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music, Sung has performed throughout the world, collaborating with soloists such as Hilary Hahn, Leila Josefowicz, and Julius Baker, longtime principal flutist with the New York Philharmonic. As a techie and entrepreneur, Hugh Sung was one of the first professional musicians to imagine performances utilizing digital music scores (beginning with Microsoft’s Tablet PC in 2001). In 2008, he co-founded AirTurn, a company that develops a host of cutting-edge tech gadgets for musicians, including wireless page turning pedals. He is the author of From Paper to Pixels: Your Guide to the Digital Sheet Music Revolution. As a teacher, Sung, who served for 19 years on the Curtis faculty, has reached out to long distance students through Video Exchange Learning technology from ArtistWorks.

Now Hugh Sung is engaging with classical music enthusiasts in yet a new way. On Monday, he launched A Musical Life with Hugh Sung, a collection of weekly podcasts featuring fascinating interviews with renowned musicians. He describes it as, “sharing stories about making music and the things that move our souls.”

A Musical Life has hit the ground running with an eclectic collection of offerings already in place. Philadelphia Orchestra concertmaster David Kim opens up about his journey through the competitive world of classical music, from early disappointments and insecurities to finding ultimate joy and satisfaction in serving music. Sung does a two-part interview with legendary violinist Aaron Rosand, whom Sung first met as a student at Curtis and later joined as a collaborator. Rosand talks about the distinctive individuality of “golden age” violinists such as Jascha Heifetz, the role of the bow in tone production, the sound of his ex-Kochanski Guarneri del Gesù, his love of old jazz, and more. Other interviews include pianist Gary Graffman, Gaelic singers Isobel Ann and Calum Martin, and Jordan Rudess, a member of the progressive rock band, Dream Theater. In the first episode, A Lonely Song, Sung shares thoughts about the second movement of Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G major.

A Musical Life is extraordinary, not only because of Hugh Sung’s musical background, but because of his talent as an interviewer. He is sincere and down to earth, asking all the right questions and allowing the discussion to unfold naturally. As a listener, you feel as if you’re sitting in a comfortable room with friends. As musical examples are discussed, we get to hear excerpts from the artists’ recordings. Enjoyable now, these interviews will live on as fascinating historical documents. It will be exciting to follow the podcasts at A Musical Life in the weeks ahead.

[hr]

Hugh Sung and Aaron Rosand

Hugh Sung first met violinist Aaron Rosand as a student at the Curtis Institute. Later, Rosand and Sung collaborated on a series of recordings.

Here is excerpt from their 2007 recording of the three Brahms Violin Sonatas. (Brahms’ Hungarian Dances and Joachim’s Romance in B-flat are also included on the disc). This is the first movement of Brahms’ Sonata No. 1 in G:

Here is a beautiful and rarely-heard piece from Rosand and Sung’s 2011 recording featuring Romances for violin: Sibelius’ Romance, Op. 78, No. 2.

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find Hugh Sung’s recordings at iTunes, Amazon.

- Find other Aaron Rosand recordings at iTunes, Amazon.

[/unordered_list]