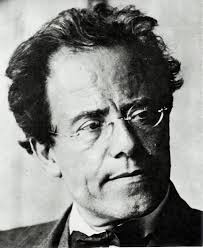

Earlier in the month, we listened to the final movement of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, a song cycle about death, renewal, and immortality. Written in the final years of Mahler’s life, Das Lied von der Erde, along with the Ninth Symphony (completed in 1909), were Mahler’s swan songs. (He completed one movement of a Tenth Symphony before his death in 1911). Both completed works leave us with a sense of finality, not with the joyful, celebratory exuberance of Beethoven’s Ninth, but instead quietly fading into a sea of eternal peace. There’s something unsettling, even terrifying about the ending of both, but at the same time there is a sense of liberation in letting go.

Earlier in the month, we listened to the final movement of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, a song cycle about death, renewal, and immortality. Written in the final years of Mahler’s life, Das Lied von der Erde, along with the Ninth Symphony (completed in 1909), were Mahler’s swan songs. (He completed one movement of a Tenth Symphony before his death in 1911). Both completed works leave us with a sense of finality, not with the joyful, celebratory exuberance of Beethoven’s Ninth, but instead quietly fading into a sea of eternal peace. There’s something unsettling, even terrifying about the ending of both, but at the same time there is a sense of liberation in letting go.

We’ll explore Mahler’s Ninth Symphony in a future Listeners’ Club post. But for now, here are four other pieces which say “goodbye” in their own unique ways:

Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony

Tchaikovsky’s final symphony is one of music history’s most famous and dramatic “goodbye’s.” It’s music that seems to give up in anguished resignation. Following the exhilaration of the third movement (which ends with such a bang that audiences often can’t help but applaud), the fourth and final movement immediately plunges us into the depths of despair. Tchaikovsky conducted the premiere nine days before his death. Some listeners have been tempted to view this symphony as the composer’s suicide note. No historical evidence exists to back up such a romanticized reading. Besides, truly great music is never biographical. It always transcends the literal.

Each movement of the Sixth Symphony features a descending scale. In the final movement’s second theme, this descending motive takes on new prominence. We hear it in the last bars, which are marked, morendo (“dying away”). In the ultimate descent, the instruments of the string section gradually drop out until only the lowest voices are left. When I play this music in the second violin section, I’m always struck by a visceral sense of the music going underwater and remaining unresolved, as the scale line (B, B, A, G, F-sharp) makes it to G, the lowest note on the violin, but can’t go further.

Here is the final movement performed by Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic:

Dvořák’s Cello Concerto

Antonín Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in A Major, completed in 1895 while Dvořák was in New York, is a musical elegy. It’s music which wistfully revisits distant memories, pays respect, and then rises into blazing triumph.

Shortly after completing the cello concerto, Dvořák learned that his sister-in-law, Josefina Kaunitzová, had passed away. 30 years earlier he had been in love with Josefina. She had not returned the feelings, and Dvořák ultimately married Josefina’s younger sister, Anna. In the second movement, Dvořák quoted one of his earlier songs, Kez duch muj san”(“Leave me alone”), which had been a favorite of Josefina. (Listen to that beautiful melody here). The third movement, peppered with fiery Czech folk rhythms, appears to be propelling towards a conventional conclusion, when suddenly in the movement’s coda, all of the forward drive dissipates and we find ourselves in a moment of tender introspection (beginning at 35:39 in the clip below). When the soloist, Hanuš Wihan, attempted to add a cadenza in the third movement’s coda, Dvořák would not permit it, writing,

I give you my work only if you will promise me that no one – not even my friend Wihan – shall make any alteration in it without my knowledge and permission, also that there be no cadenza such as Wihan has made in the last movement; and that its form shall be as I have felt it and thought it out.

He went on to offer the following description:

The Finale closes gradually diminuendo, like a sigh, with reminiscences of the first and second movements—the solo dies down . . .then swells again, and the last bars are taken up by the orchestra and the whole concludes in a stormy mood. That is my idea and I cannot depart from it.

Here is a 1964 recording with Leonard Rose and the Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Eugene Ormandy:

Strauss’ Metamorphosen

Richard Strauss’ ultimate musical “goodbye” was the Four Last Songs, written in 1948, a year before his death. But a few years earlier, in 1945, Strauss’ Metamorphosen became a farewell to the pre-war world he had known, and perhaps even the long arc of Romanticism which had begun with Beethoven. The work for string orchestra was begun the day after allied bombing destroyed the Vienna Opera House. It quotes the funeral march from Beethoven’s Eroica, although Strauss claimed that the reference only became apparent to him after the score’s completion. Two verses from Goethe’s poem, Widmung (“Dedication”) also served as inspiration.

Strauss initially attempted to placate the Nazis, partly in an attempt to protect his Jewish daughter-in-law and grandchildren. He believed he could survive this regime, as he had others before it. A few days after completing Metamorphosen, he wrote,

The most terrible period of human history is at an end, the twelve year reign of bestiality, ignorance and anti-culture under the greatest criminals, during which Germany’s 2000 years of cultural evolution met its doom.

Here is a 1973 Staatskapelle Dresden recording, conducted by Rudolf Kempe:

Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra

Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra, written in 1943 two years before the composer’s death, says “goodbye” in a strikingly different way than Tchaikovsky’s Sixth. Amid rapidly failing health and poverty, Bartók wrote this monumental work as a commission for conductor Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony.

The final movement soars with exuberance, celebrating the full virtuosic possibilities of the orchestra. Eastern European folk rhythms dance alongside a fugue, one of the most sophisticated musical structures. It’s hard to imagine any music more full of life. The last chord lets out one final, joyful yelp as it reaches for the stars.

Here is the fifth movement of Concerto for Orchestra, from a recording by Sir Georg Solti and the Chicago Symphony:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 in B minor, “Pathétique” at iTunes, Amazon.

- Find Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in A Major at iTunes, Amazon.

- Find Strauss’ Metamorphosen at iTunes, Amazon.

- Find Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra at iTunes, Amazon.

[/unordered_list]