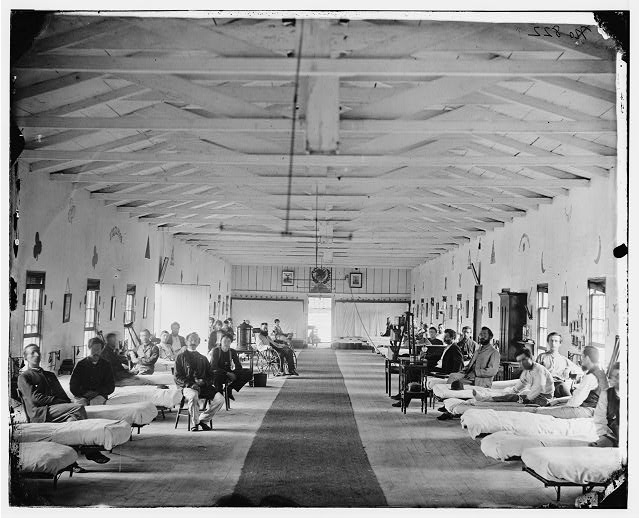

Thus in silence in dreams’ projections,Returning, resuming, I thread my way through the hospitals,The hurt and wounded I pacify with soothing hand,I sit by the restless all the dark night, some are so young,Some suffer so much, I recall the experience sweet and sad,(Many a soldier’s loving arms about this neck have cross’d and rested,Many a soldier’s kiss dwells on these bearded lips.)

-Walt Whitman, The Wound-Dresser, 1865

On July 21, 1861, spectators, armed with picnic baskets, eagerly followed the Union army twenty five miles out of Washington into the Virginia countryside to watch what would become the first major battle of the American Civil War. At the First Battle of Bull Run, Northern sightseers (including congressmen) expected to observe a quick, easy, and decisive victory over the Confederates…perhaps the nineteenth century equivalent of “shock and awe.” They intended to indulge romantic notions of heroism and valor. Instead, they got a glimpse of the horrific reality of war. Bull Run was the bloodiest battle in American history up to that point. It showcased the gruesome and unexpected effects of new combat technology. Notions of a quick “summer war” were swept away and for both sides Bull Run suddenly became a depressing harbinger of the struggle ahead. The poorly trained defeated Union army fled back to Washington amid the gridlock of sightseers.

The poet Walt Whitman (1819-1892) forces us to confront the human cost of war. “The real war will never get in the books” said Whitman, who dressed the wounds of both Northern and Southern soldiers during the Civil War. But enter the dazed world of The Wound-Dresser and other war poems by Whitman, and you begin to get a sense of the wasteland of the battlefield. Out of this darkness emerges a powerful sense of humanity: the loving relationship between caregiver and dying patient. As Sarah Cahill observes,

There is a powerful tension in Whitman’s poem between the physical and the metaphysical, between bodily sickness, which he records with almost scientific detachment (“From the stump of the arm, the amputated hand/I undo the clotted lint”) and a spiritual transcendence of the corporeal.

In John Adams’ 1988 setting of Whitman’s poem, we get a sense of the wound dresser going about his business in a daze. The hypnotic repetition of the opening music and the detached, searching voice of the solo violin in its highest and most ethereal register create the feeling of an out-of-body experience. Surreal new electronically synthesized sounds blend with the traditional orchestra. Suppressed emotion and scientific detachment seem to be the only way to survive the horrific work at hand. But there are also brief moments of intense, soaring emotional release. Later, we hear the searching sound of a distant battlefield bugle (11:02), the same voice we hear in Adams’ haunting, quiet fanfare, Tromba lontana.

John Adams’ vocal lines preserve the rhythmic flow of Whitman’s poem. In an interview with Edward Strickland (American Composers: Dialogues on Contemporary Music) Adams said,

I tried to set the Wound-Dresser absolutely simply and used hardly any melisma, since American English does not lend itself well to that treatment, as Italian or even German does. The best American pop and Broadway music by very great composers like Richard Rodgers and George Gershwin had the ability to treat the text in a very direct way, and that’s the tact I’ve taken in this piece.

Here is a performance by the Orchestra of St. Luke’s with baritone Sanford Sylvan:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_r8knyk-T2M

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

[hr]

George Crumb’s Apparition

West Virginia composer George Crumb’s Apparition for Soprano and Amplified Piano (1979) is a setting of Walt Whitman’s famous elegy following the assassination of Lincoln, When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d. We float through a strange, cinematic musical landscape with a surprising array of sounds and colors emerging from the piano. William Bland provides this description in the program notes to this recording:

. . . the literary and musical materials focus on concise, highly contrasting metaphors for existence and death . . . death is never depicted as an ending of life. Instead, it is circular, always beginning or an enriched return to a universal life-force . . .

Here are three excerpts performed by mezzo-soprano Jan DeGaetani, (for whom the piece was written), and pianist Gilbert Kalish:

1. The Night in Silence Under Many a Star:

3. When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d:

8. Come Lovely and Soothing Death:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Paul Hindemith’s Requiem

Here is German composer Paul Hindemith’s When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d: A Requiem for those we love, written in 1946, following the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt:

https://youtu.be/cWbcm76TWAo?list=PLF689EADE8508A12F

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

“Be not dishearten’d — Affection shall solve the problems of Freedom yet;

Those who love each other shall become invincible.”

-Walt Whitman, Over the Carnage Rose Prophetic a Voice