The lullaby is universal and timeless. It’s one of the clearest expressions of the deep bond between mother and young child. Its gentle, repetitive, rocking rhythm lulls infants to sleep. The simple expression of its melody evokes warmth and security. At the same time, many lullabies contain an inexplicable hint of sadness.

From Franz Schubert to George Gershwin to U2, music history is full of lullabies. Here are five of my favorites:

Schubert’s Wiegenlied, Op. 98, No. 2

We’ll begin with the simple perfection of Franz Schubert’s Wiegenlied, Op. 98, No. 2, written in November, 1816. You can read the text here. Listen to the way this performance by mezzo-soprano Janet Baker and pianist Gerald Moore fades into sleepy oblivion:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N2zXK-qyOXQ

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Brahms’ Wiegenlied, Op. 49, No. 4

Johannes Brahms may have written the world’s most famous lullaby. Wiegenlied, Op. 49, No.4 was dedicated to Brahms’ former lover, Bertha Faber, after the birth of her son. The melody found its way into the first movement of Brahms’ Second Symphony in a slightly altered form. You can hear it at this moment about four minutes into the movement.

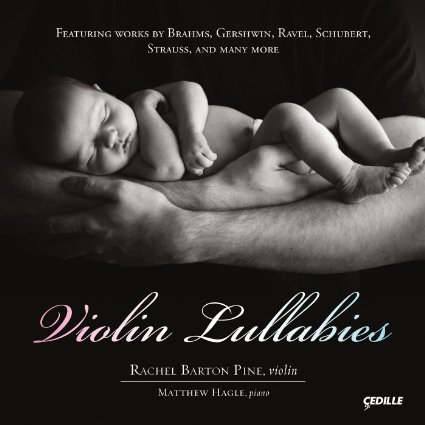

Violinist Rachel Barton Pine included a transcription of the Brahms Lullaby on her 2013 Violin Lullabies album (pictured above).

The text is from Des Knaben Wunderhorn, a collection of German folk poems which inspired composers from Schumann and Mahler to Webern. Here is a performance by Anne Sofie von Otter and pianist Bengt Forsberg. Notice the gentle rocking rhythm and hypnotic repetition of the tonic in the piano line.

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Julie’s Lullaby from Dvořák’s “The Jacobin”

Antonín Dvořák’s rarely performed 1889 opera, The Jacobin, is set in Bohemia around the time of the French Revolution. The aging Count Harasova is preparing to hand over power to his nephew, Adolf. Harasova has disowned his son, Bohuš who has just returned home from Paris with a French wife, Julie. The scheming Adolf has convinced Harasova that Bohuš is a dangerous revolutionary, allied with the Jacobins. By the end of the opera, Count Harasova realizes that he has been deceived and proclaims Bohuš to be his true successor.

In Act III, Scene V, Count Harasova hears Julie sing Synáčku, můj květe (“Son of mine, mine flower”). It’s a lullaby that the late Countess sang to Bohuš as a child, many years earlier. In the opening of the aria, the sound of the horn seems to take on mystical significance, as if preparing us for the dreamscape of nostalgia and memory which follows.

Julie’s Lullaby enters the same magical Bohemian folk world we hear in Mahler’s Songs of a Wayfarer, completed around the same time, in 1885. As in the Mahler, Dvořák’s aria conjures up a complex and confusing mix of indescribable, but powerful emotions. Notice the way the music slips between major and minor.

Here is Eva Randova and the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Busoni’s Berceuse élégiaque

Ferruccio Busoni’s haunting Berceuse élégiaque turns the lullaby on its head with the subtitle, “The man’s lullaby at his mother’s coffin.” Written in 1909, the first performance was given by the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall on February 21, 1911 with Gustav Mahler conducting. Mahler must have felt strongly about this music because he insisted on conducting, despite a fever of 104. It was his final concert. He returned to Vienna and died three months later.

The rocking rhythm at the opening of this piece is similar to what we heard in Brahms’ Lullaby, but this is an entirely different world. In the opening, dark, murky string colors suggest the feeling of being under water.

Here is a 2010 performance by Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Ed Spanjaard:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Ravel’s Berceuse sur le nom de Gabriel Fauré

Maurice Ravel wrote this short lullaby in 1922 as a tribute to the 77-year-old Gabriel Fauré. The piece’s motive grew out of Fauré’s name (GABDBEE FAGDE). Behind the music’s innocence and simplicity lies a hint of something dark and ominous. But, like so much of Ravel’s music, we only catch a glimpse of the storm clouds. The piece concludes with a sense of joyful, child-like detachment. It’s like watching a young child who is completely absorbed in the imaginary world of play. The final bars evaporate into a dreamy haze.

This performance comes from a recording by violinist Chantal Juillet and pianist Pascal Rogé:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xDw-ZxD_3gk

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

[hr]

Hush, little one, and fold your hands;

The sun hath set, the moon is high;

The sea is singing to the sands,

And wakeful posies are beguiled

By many a fairy lullaby:

Hush, little child, my little child!Dream, little one, and in your dreams

Float upward from this lowly place,–

Float out on mellow, misty streams

To lands where bideth Mary mild,

And let her kiss thy little face,

You little child, my little child!Sleep, little one, and take thy rest,

With angels bending over thee,–

Sleep sweetly on that Father’s breast

Whom our dear Christ hath reconciled;

But stay not there,–come back to me,

O little child, my little child!

-Emily Dickinson (Sicilian Lullaby)

French impressionist composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) found inspiration in the American jazz, which was

French impressionist composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) found inspiration in the American jazz, which was