It’s that time of year again…time for the annual Listeners’ Club Christmas playlist. As with last year’s post, this is a collection of music guaranteed to get you in the holiday spirit. Pour some eggnog, light the tree and listen:

Thomas Tallis: Christmas Mass

We’ll start with music written for an important political occasion. The Christmas Mass by English composer Thomas Tallis (c. 1505-1585) may have been written for Christmas Day, 1554 when Phillip II of Spain was in England to wed Queen Mary. Here is the opening Gloria:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9auVnJdHE7E

J.S. Bach: Christmas Oratorio

J.S. Bach’s Christmas Oratorio was written for Christmas Day, 1734. This quiet, pastoral Sinfonia opens the second of the six parts. (Listen to the entire piece here). There’s an incredible intimacy to this music. Listen to the way the strings establish the atmosphere and then fade away, leaving us with the sound of shepherds in a calm pasture:

Rimsky-Korsakov: Christmas Eve

Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov created this orchestral suite with music from his 1895 opera, Christmas Eve. The opera’s plot is based on Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, a collection of short stories by Nikolai Gogol. The suite is in five movements: Christmas Night, Ballet of the Stars, Witches’ Sabbath and Ride on the Devil’s Back, Polonaise, and Vakula and the Slippers.

Rimsky-Korsakov was one of the most imaginative and colorful orchestrators. Just listen to the way the tone colors shift and change subtly in the opening chords, evoking a sense of mystery. This music glistens with bright Christmas lights in a way which might remind you of a Hollywood film score. If you’re familiar with Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade or Russian Easter Overture, you’ll be reminded of those pieces. But there’s also one moment which, for me, suggests a surprising link between Rimsky-Korsakov and Sergei Prokofiev. (Prokofiev studied orchestration briefly with Rimsky-Korsakov). This melody, with its unpredictable harmonic turns and off-balance rhythm, feels as if it stepped out of one of Prokofiev’s ballet scores.

Prokofiev: Troika from “Lieutenant Kije”

The Troika movement from Sergei Prokofiev’s score to the 1934 film, Lieutenant Kije has long been associated with Christmas. A troika is a Russian horse-drawn sleigh. You could call this a “short ride in an equestrian machine.”

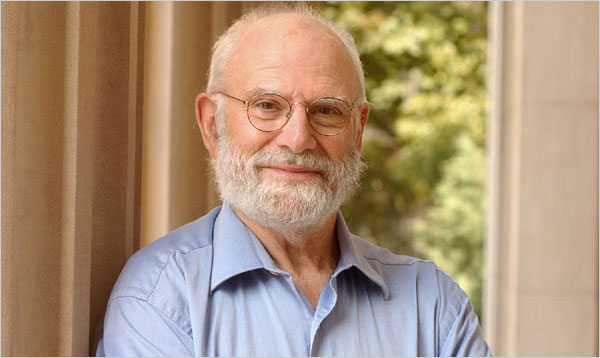

Sir David Willcocks: Sussex Carol

Let’s finish where we started back in England. Here is Sir David Willcocks’ arrangement of Sussex Carol. Willcocks, who passed away in September, was the longtime director of the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge.

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find Thomas Tallis’ Christmas Mass at iTunes, Amazon. The recording above is performed by the Tallis Scholars.

- Find J.S. Bach’s Christmas Oratorio at iTunes, Amazon.

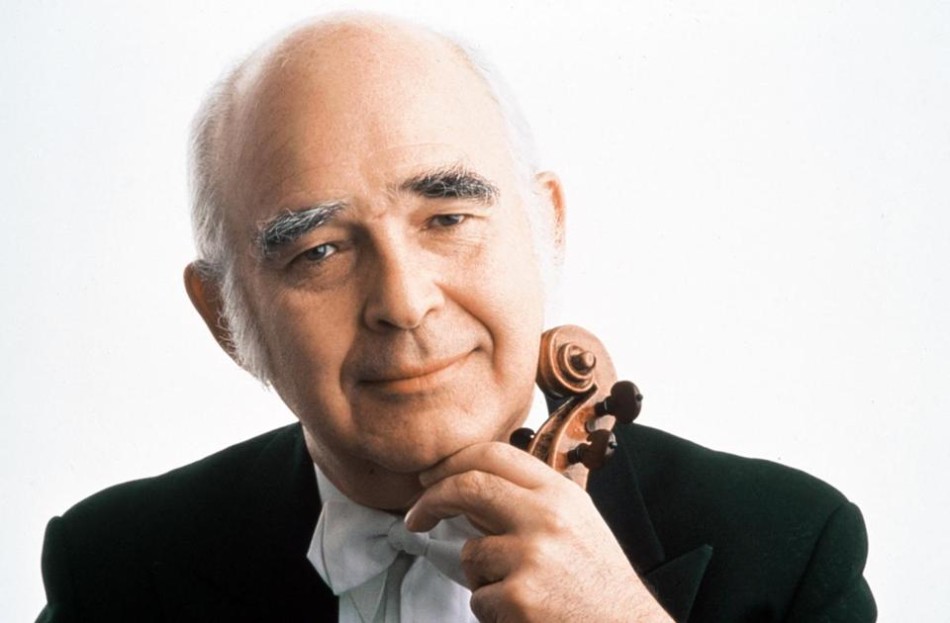

- Find Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s Christmas Eve at iTunes, Amazon. The recording above features Neeme Järvi and the Scottish National Orchestra.

- Find Prokofiev’s Lieutenant Kije at iTunes, Amazon.

- Find Sir David Willcocks’ arrangement of Sussex Carol at iTunes, Amazon.

[/unordered_list]