Johannes Brahms’ Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77 stands with Beethoven’s Concerto at the pinnacle of the violin repertoire. No concerto unleashes the soaring, heroic power and poetic potential of the violin more profoundly than Brahms’. It’s music that runs the gamut between smoldering ferocity and tranquil introspection, encompassing a universe of expression.

Brahms’ forty-plus year friendship and musical partnership with the German violinist and composer Joseph Joachim (1831-1907) was central to the Violin Concerto’s inception. Beginning with an August 21, 1878 correspondence, Joachim offered Brahms technical and musical advice after seeing sketches of the concerto, which was originally conceived in four movements. With Brahms conducting (inadequately), Joachim gave a hastily prepared and technically insecure premiere on January 1, 1879 at the Leipzig Gewandhaus. This was followed by another slightly more successful performance in Vienna. But even Brahms’ most dedicated supporters, such as Joachim and the powerful Vienna critic Eduard Hanslick, seem to have needed time to warm up to the new composition. This initial lukewarm public reception and Joachim’s complaints of “awkward” violin passages show how profoundly Brahms’ Concerto pushed the envelope musically and in terms of violin technique. As affection for the work grew, Brahms wrote to a friend:

Joachim plays my piece more beautifully with every rehearsal, and his Cadenza has become so beautiful by concert time that the public applauded into my Coda.

As a composer, Brahms was haunted by the “footsteps of a giant,” Beethoven, whose music had profoundly changed the course of music history. Following the example of the Beethoven Violin Concerto, Brahms’ Concerto is set in D major and opens with a long orchestral introduction. From the opening of the first movement, there’s a sense that the music is searching for a way forward. Following the opening statement, the oboe takes us in a new, unexpected direction. Then, resolute octaves turn into chords and suddenly we know where we are. In the passage that follows, listen closely to the canon that develops between the high and low strings. The first movement’s introduction concludes with a ferocious buildup to the violin’s entrance. Notice the rhythmic instability Brahms sets up in the low instruments, which causes us to lose track of the downbeat. You’ll hear Brahms play these occasional rhythmic games throughout the movement, especially in the final bars.

The solo violin explodes onto the scene with its first entrance, as if unleashing all of the introduction’s tension. Listen to the way the strings snarl back at the solo line in this opening. The way the solo and orchestral voices fit together is a huge part of the drama of this piece. Joseph Hellmesberger, who conducted the Vienna premiere, accused Brahms of writing a concerto, “not for, but against the violin.”

One of this concerto’s most serenely beautiful moments is the first movement’s coda, following the cadenza. In these bars, time seems suspended and we almost hold our breath as the final tutti is delayed. Just when we think the violin can’t reach higher, it somehow does. As the movement inches towards its final resolution, listen to the quiet, suspended fanfare in the horns and woodwinds.

The second movement opens with one of the most tranquil and sublime oboe solos in orchestral music. This extended statement is the last thing we would expect in a violin concerto. The Spanish virtuoso, Pablo de Sarasate complained that he refused to “stand on the rostrum, violin in hand and listen to the oboe playing the only tune in the adagio.”

The final movement is a sparkling, fun-loving romp. You can hear echoes of the final movement of Max Bruch’s First Violin Concerto. Brahms’ opening theme apparently served as a model for Andrew Lloyd Webber’s pop song, Don’t Cry for me, Argentina from the musical, Evita.

[hr]

Eight Great Recordings

Here are eight contrasting recordings of the Brahms Violin Concerto. Explore the list and then share your thoughts in the comment thread below. If you have a favorite recording that didn’t make the list, leave your own suggestion below.

Henryk Szeryng and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra

Henryk Szeryng’s 1974 recording with Bernard Haitink and Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra is one of the most inspiring recordings I’ve heard of this piece. There is a straightforward classicism to his approach. At the same time, the drama of the music shines through. The tempos on this recording capture the expressive weight of the music. Szeryng plays Joachim’s cadenzas:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

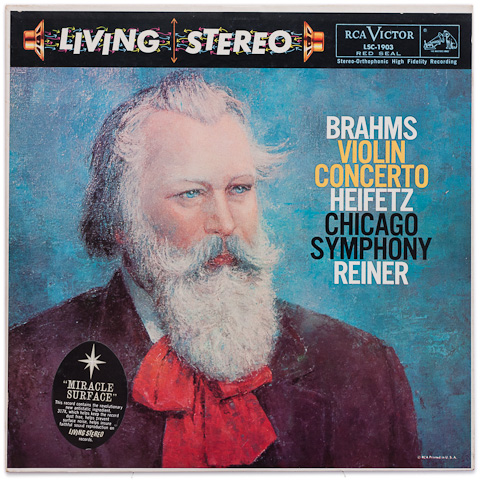

Jascha Heifetz and the Chicago Symphony

This classic 1959 Heifetz recording, with Fritz Reiner conducting the Chicago Symphony, was my first introduction to the piece as a child. The searing intensity of this performance is unparalleled. With Heifetz’s trademark fast tempos, this is one of the most exciting, yet soulful performances you’ll hear:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Hilary Hahn and the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields

If you’re looking for a modern performance, you won’t go wrong with Hilary Hahn’s 2001 recording with Sir Neville Marriner and the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields. The motto of this CD might be, “opposites attract,” because the Brahms is coupled with an equally great performance of the Stravinsky Violin Concerto.

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Bronislaw Huberman and the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York

This historic, live 1944 recording of Bronislaw Huberman and conductor Artur Rodzinski in New York offers a unique slice of history. As a child, Huberman played the concerto in Brahms’ presence in Vienna in January, 1896. According to the biographer Max Kalbeck:

As soon as Brahms heard the sound of the violin, he pricked up his ears, during the Andante he wiped his eyes, and after the Finale he went into the green room, embraced the young fellow, and stroked his cheeks. When Huberman complained that the public applauded after the cadenza, breaking into the lovely Cantilena, Brahms replied, “You should not have played the cadenza so beautifully”…Brahms brought him a photo of his, inscribed, “In friendly memory of Vienna and your grateful listener J. Brahms.”

In his book, Great Masters of the Violin, Boris Schwarz recounts that someone overheard Brahms promise to write a short violin fantasy for the young Huberman, adding jokingly, “if I have any fantasy left.” But Brahms died the following year.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iOR6YSByk70

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Julia Fischer and the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra Amsterdam

Julia Fischer’s 2006 recording with conductor Yakov Kreizberg is the most recent CD on the list. Fischer offers a Romantic and introspective reading, filled with mystery. The disk includes Brahms’ “Double” Concerto with German cellist Daniel Müller-Schott.

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Anne-Sophie Mutter and the New York Philharmonic

Anne-Sophie Mutter recorded the Brahms early in her career with Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic (listen here). It’s interesting to compare that more straightforward interpretation with her later 1997 recording with Kurt Masur and the New York Philharmonic. The later recording is definitely more romantic with more emphasis on vibrato. Mutter’s dynamic range is also remarkably wide. I’d be interested in hearing your thoughts on which version you prefer.

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

David Oistrakh and the French National Radio Orchestra

Few “great recordings” lists are complete without a performance by David Oistrakh. Oistrakh recorded the Brahms Concerto several times. Otto Klemperer conducted this reverberant 1960 studio recording.

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Ruggiero Ricci and the Sinfonia of London

This 1991 Ruggiero Ricci CD features sixteen cadenzas including those written by Ferruccio Busoni, Leopold Auer, Eugène Ysaÿe, Fritz Kreisler, Adolf Busch, and Nathan Milstein.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KVr2Q4NUcNo

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

The key of C minor held special significance for Beethoven. Emotionally intense and stormy, C minor evoked the turbulence of an age of revolution. It embodied a sense of heroic struggle, which would form the bedrock of Romaticism.

The key of C minor held special significance for Beethoven. Emotionally intense and stormy, C minor evoked the turbulence of an age of revolution. It embodied a sense of heroic struggle, which would form the bedrock of Romaticism.