The Listeners’ Club wishes Yo-Yo Ma, who turns 60 today, a happy birthday.

Ma is one of a handful of front-rank musicians who can be described as a cultural ambassador. Over the years, he has been at home, not only at Carnegie Hall but also on Sesame Street (watch “The Jam Session,” “The Honker Quartet,” and “Elmo’s Fiddle Lesson”), Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and at a presidential inauguration. At the age of seven he performed for President John F. Kennedy. On Monday he appeared with dancer Misty Copeland on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, setting Twitter abuzz.

Beethoven’s Cello Sonatas

Here is Yo-Yo Ma’s recording, with pianist Emanuel Ax, of Beethoven’s complete Sonatas for Cello and Piano, first released in 1987. At times shrouded in mystery and fire, this is music which captures the soul of the cello. Beethoven was the first major composer to write sonatas in which the cello and piano are equals. The early sonatas were written in 1796. The “Late Sonatas” were written in 1815.

Listen to Volume 2 and 3 to hear the complete set of sonatas.

Shostakovich’s First Cello Concerto

Here is Dmitri Shostakovich’s ferocious First Cello Concerto (written in 1959 and dedicated to Mstislav Rostropovich) from a 1983 recording with the Philadelphia Orchestra and conductor Eugene Ormandy.

From the taunting opening, the music is imprinted with the “DSCH” motive, Shostakovich’s initials translated into their corresponding pitches in German musical notation: D, E-flat, C, B natural. (In German notation Es is E-flat and H is B.), The four note “DSCH” motive defiantly appears throughout other Shostakovich scores. (See this earlier Listeners’ Club post). There are echoes of Shostakovich’s 1948 score for the film, The Young Guard, which depicts the execution of Soviet soldiers by the Nazis. The Concerto also directly quotes a dark lullaby, sung to a sick child by Death (disguised as a caretaker), in Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death.

The first movement is propelled forward by an unrelenting, and almost inhuman, bass line. Amid sardonic statements from the woodwinds, the music feels simultaneously comic and terrifying. The sombre second movement, given the simple marking, Moderato, opens as a lament, gradually building into a prolonged scream of anguish. Here, in the Concerto’s interior, away from the sarcasm of the outer movements, we’re able to glimpse the music’s most profound and terrifying essence. The movement concludes with haunting stillness (beginning at 14:52). After descending into a lonely, prolonged cadenza (the third movement), we’re plunged into a fiery dance (the fourth movement).

The Swan

We’ll conclude with the serene beauty of The Swan from Camille Saint-Saëns’ The Carnival of the Animals:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DK3u9GLEe18

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find Yo-Yo Ma’s recordings at iTunes, Amazon.

- Go behind the scenes with concert and rehearsal footage recorded throughout Yo Yo Ma’s career and watch the 2010 documentary, Classic Yo-Yo Ma.

- Art for Live’s Sake: In Conversation with Yo-Yo Ma

[/unordered_list]

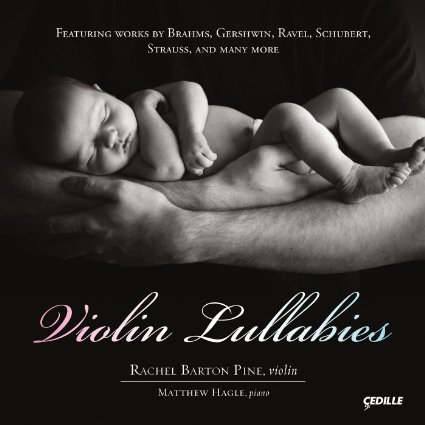

The lazy days of summer are here in the Northern Hemisphere. For many of us this is a time to rest and recharge, whether in the cool shade of a back yard hammock or the sun and sand of the beach. What music could be more appropriately relaxing and soothing than a lullaby, with its gentle rocking rhythm and simple repetitive melody?

The lazy days of summer are here in the Northern Hemisphere. For many of us this is a time to rest and recharge, whether in the cool shade of a back yard hammock or the sun and sand of the beach. What music could be more appropriately relaxing and soothing than a lullaby, with its gentle rocking rhythm and simple repetitive melody?