Washington’s Birthday, the first movement of Charles Ives’ Holiday Symphony, emerges out of the desolate, snowy gloom of a midwinter night in rural New England. The music feels strangely amorphous, as if we’ve suddenly slipped into a dream.

As we enter this sonic dreamscape, it’s easy to get the sense that we’re joining music already in progress. Who knows where or when it began? Drifting from one hazy moment to the next, we gradually become aware of a growing hubbub of voices. Suddenly, we find ourselves in the middle of a spirited barn dance. Fragments of old American folk melodies float in and out of our consciousness and begin to blend into a growing, joyful cacophony. With one shocking, climactic chord, our strange dream shows signs of turning into a nightmare. But then, just as suddenly, the night begins to wind down. Amid the final echoes of a fragment of Goodnight, Ladies, our ephemeral vision evaporates…

Here are the opening lines of Charles Ives’ description of Washington’s Birthday:

Cold and Solitude,” says Thoreau, “are friends of mine. Now is the time before the wind rises to go forth to seek the snow on the trees.”

And there is at times a bleakness without stir but penetrating, in a New England midwinter, which settles down grimly when the day closes over the broken-hills. In such a scene it is as though nature would but could not easily trace a certain beauty in the sombre landscape!–in the quiet but restless monotony! Would nature reflect the sternness of the Puritan’s fibre or the self-sacrificing part of his ideals?

Leonard Bernstein’s recording with the New York Philharmonic:

Visit Listeners’ Club posts featuring other movements from Ives’ Holiday Symphony, Thanksgiving Day, and Decoration Day.

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find this recording on iTunes

- Find this recording at Amazon

- Watch Michael Tilson Thomas’ Keeping Score episode

[/unordered_list]

Written in 1909

Composed in 1909 and revised and published four years later, Washington’s Birthday is an adventurous journey into atonality. Similar music was pushing the boundaries in Europe. 1909 was the year Anton Webern wrote the groundbreaking Five Movements, Op. 5. The same year, Claude Debussy began writing his twenty four Préludes for solo piano. Listen to the hazy impressionism of the second Prélude from Book 1, Voiles. This music is constructed on the same whole tone scale Ives uses in the opening of Washington’s Birthday.

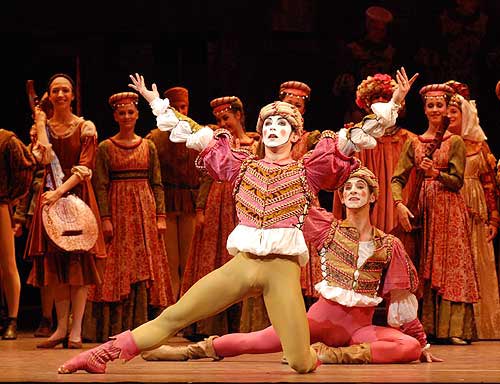

In 1909 Mahler finished Das Lied von der Erde (“The Song of the Earth”). Ravel began work on the ballet Daphnis et Chloé and Stravinsky was a year away from completing The Firebird.