Great orchestras develop an institutional collective memory. As conductors and players come and go, they often leave a subtle mark on the sound, style, and soul of the ensemble. New players are assimilated into a dynamic, ever-evolving team. The esteemed history of the Philadelphia Orchestra is a case in point.

For years the Philadelphia Orchestra was known for its distinctive, darkly opulent sound, especially evident in the lush, velvety warmth of its string section. The “Philadelphia Sound” likely emerged under the leadership of Leopold Stokowski (music director from 1912 to 1938), who discarded a baton and conducted with his enormous, expressive hands. The sound continued to develop under Eugene Ormandy (music director from 1936 to 1980). Balance favoring the bottom voices (bass and cello) seems to have contributed to tonal richness and depth. Also, the dry acoustics of the Academy of Music may have played a role in shaping the “Philadelphia Sound,” as conductors attempted to compensate for the cavernous concert hall’s weaknesses.

The old Philadelphia Orchestra never sounded more vibrant than when it was performing the music of Sergei Rachmaninov. Rachmaninov’s long association with the orchestra is one of music history’s most fascinating examples of mutual influence between a composer and orchestra. Both Stokowski and Ormandy championed Rachmaninov’s music, beginning with Stokowski’s January 3, 1913 performance of the tone poem, Isle of the Dead. Rachmaninov’s final work, the Symphonic Dances, Op. 45, first performed on January 3, 1941, was dedicated to Ormandy and the orchestra. Rachmaninov is said to have composed with the Philadelphia Orchestra’s sound in his mind. The sensuous beauty of Rachmaninov’s music surely left its imprint on the orchestra, as well.

Many excellent recordings have been made of Rachmaninov’s orchestral music in the intervening years, but there’s something uniquely soulful about the old Philadelphia recordings. Here is a sample:

Symphony No. 2

Eugene Ormandy recorded Rachmaninov’s Second Symphony four times: Once in 1934 with the Minneapolis Symphony, and again in Philadelphia in 1951, 1959, and 1973. The final recording restores the work to its original form, without Rachmaninov’s approved cuts. The performance below was a June, 1979 PBS broadcast, celebrating Eugene Ormandy’s 80th birthday. It’s amazing to watch Ormandy’s seemingly effortless sense of control. There’s nothing flamboyant or flashy in his conducting, yet he draws incredible power and warmth from the orchestra.

For Rachmaninov, the Second Symphony, written between 1906 and 1907, emerged out of uncertainty and self-doubt. Following the disastrous premiere of the First Symphony and the ensuing harsh criticism, Rachmaninov fell into debilitating long-term depression. The music transcends all of this. The Second Symphony’s melodies blossom and soar with gratitude, passion for life, and sensuality. Similar to Tchaikovsky’s Fourth and Fifth Symphonies, the first movement’s opening motive runs like a thread through the entire work.

The opening of the second movement hints at the Dies Irae (from the Roman Catholic mass for the Dead), which shows up throughout Rachmaninov’s music. Brief, passing motives throughout the movement return in later pieces, such as the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini and the Symphonic Dances (listen to the flute and clarinet lines at 18:06 and the four note motive at the end of the fugue section at 20:30).

The opening of the third movement shows us all of its cards up front, embracing us with an expansive statement of the movement’s main theme before moving away. This theme returns in the final movement at a moment when we least expect it. One of my favorite passages begins at 29:36, as the music reaches increasingly higher toward its climax. Listen to the way the horn line soars above the strings.

The final movement explodes with joyful exuberance, at moments paying homage to Tchaikovsky. We hear hints of the adventures of the previous movements, and then have a sense of spirited transcendence.

[ordered_list style=”decimal”]

- Largo — Allegro moderato 0:00

- Allegro molto 16:00

- Adagio 24:26

- Allegro vivace 35:29

[/ordered_list]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yw0wh-L_B_U

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Ormandy’s 1974 recording: iTunes, Amazon

- Ormandy’s 1959 recording: ArkivMusic

- Ormandy’s 1951 recording: iTunes

- Charles Dutoit’s 1995 recording with the Philadelphia Orchestra (excerpt)

[/unordered_list]

Piano Concerto No. 3

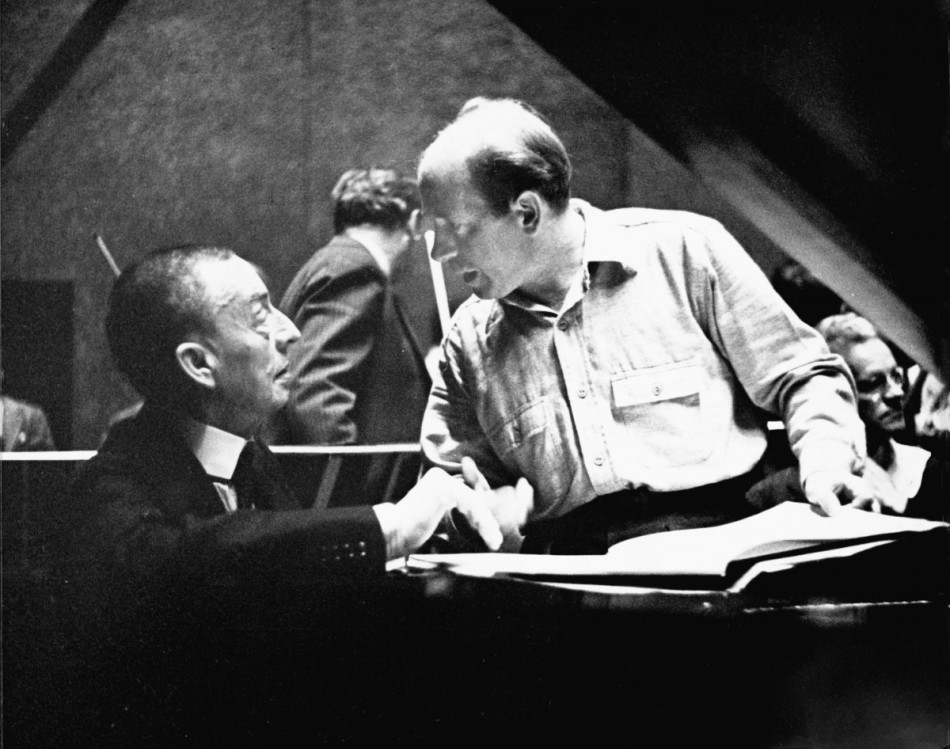

This 1939 recording features Rachmaninov performing the Piano Concerto in D minor, Op. 30, No. 3 with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra:

[ordered_list style=”decimal”]

- Allegro ma non tanto 0:00

- Intermezzo: Adagio 13:50

- Finale: Alla breve 22:26

[/ordered_list]

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Vocalise

Rachmaninov conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra for this 1929 recording. Here is Rachmaninov’s orchestral arrangement of Vocalise, Op.34 No.14:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini

Here is a December 24, 1934 recording featuring Rachmaninov performing Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43 with Leopold Stokowski conducting:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]