Venezuelan pianist Gabriela Montero is reinvigorating an old tradition: She performs all of the standard repertoire, yet she’s equally dedicated to improvising and performing her own compositions. She infuses her concerts with a refreshing sense of excitement and spontaneity, frequently improvising on melodies volunteered by the audience. The subjects of her improvisations have run the gamut from the theme from Harry Potter and “Happy Birthday” to J.S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations and Rachmaninov’s Third Piano Concerto.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, improvisation and a blurring of the line between composer and performer were common. Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Liszt were all masters of improvisation. It was only in the twentieth century (with isolated exceptions like Sergei Rachmaninov) that a gulf grew between those who created and interpreted music.

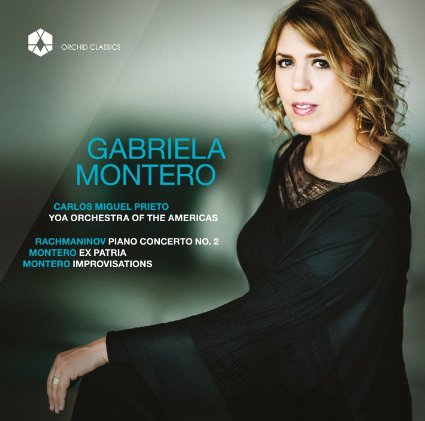

In June, Gabriela Montero released a recording of Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto, as well as her own composition, Ex Patria, and three improvisations. On the CD, she’s joined by conductor Carlos Miguel Prieto and the YOA Orchestra of the Americas, an orchestra made up of 18-30-year-old musicians from countries throughout the Western Hemisphere. Recently, Montero talked about the recording with Richmond Public Radio’s Mike Goldberg. You can hear her thoughtful and dramatic interpretation here:

Ex Patria grew out of the human rights struggle in Montero’s native Venezuela. In a recent interview, she described the piece this way:

Ex Patria I wrote in 2011 to honor the 19,336 victims of homicide that year in Venezuela. Now, to put it in perspective, that number — 19,336 — that was in 2011. Last year, there were 25,000 murders in Venezuela. So, Ex Patria was meant to be a vehicle to express all of this. I wanted people to feel what we feel as a society, a collapsed society. There is no law, there is no justice. Ninety-five percent of crimes go unresolved or unpunished. And I not only wanted to speak of numbers with my audiences but also to write a piece that would emotionally convey the message that they would be attached to. So when they left the concert hall or listened to the recording, it would be in them, it would be an experience that they could identify with. It’s very violent but also very beautiful. And it’s really a photograph of Venezuela in the last 16 years.

The three improvisations which round out this CD draw together elements from the preceding music. Montero describes the first improvisation as Baroque in nature, the second evokes Rachmaninov, and the third is an aural snapshot of Venezuela.

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find this recording at iTunes, Amazon.

- Find other recordings by Gabriela Montero.

- Watch a documentary about Ex Patria.

[/unordered_list]

Tomorrow is the first day of spring. With warmer temperatures, blooming foliage and a sense of renewal, spring has long been a rich source of poetic inspiration. Here are three songs by Franz Schubert (1797-1828) which feature spring:

Tomorrow is the first day of spring. With warmer temperatures, blooming foliage and a sense of renewal, spring has long been a rich source of poetic inspiration. Here are three songs by Franz Schubert (1797-1828) which feature spring: The greatest composers serve as visionaries and prophets, giving us a glimpse at a higher reality. Looking back through music history, many composers seem to have experienced a sharpening of this sense of vision in the final years of life. The Ninth and final symphonies of Mahler and Bruckner are filled with mystery, foreboding and spirituality. The first movement of Bruckner’s Ninth is marked “Feierlich“ (Solemn) and ” misterioso.” Schubert’s Ninth Symphony, “The Great”, is a sublime Romantic statement which, in scale, eclipses all of his previous classical symphonies. In his book, Free Play: The Power of Improvisation in Life and the Arts, Stephen Nachmanovitch writes about late Mozart:

The greatest composers serve as visionaries and prophets, giving us a glimpse at a higher reality. Looking back through music history, many composers seem to have experienced a sharpening of this sense of vision in the final years of life. The Ninth and final symphonies of Mahler and Bruckner are filled with mystery, foreboding and spirituality. The first movement of Bruckner’s Ninth is marked “Feierlich“ (Solemn) and ” misterioso.” Schubert’s Ninth Symphony, “The Great”, is a sublime Romantic statement which, in scale, eclipses all of his previous classical symphonies. In his book, Free Play: The Power of Improvisation in Life and the Arts, Stephen Nachmanovitch writes about late Mozart: