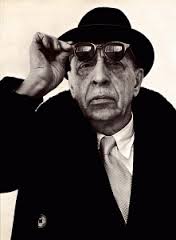

Good composers borrow. Great ones steal.

-Igor Stravinsky

La Folia, the ancient theme/chord progression which originated in Portuguese dance music as early as 1577, was borrowed (and stolen) by composers throughout the Baroque era. Vivaldi, Scarlatti, Handel, and Jean-Baptiste Lully were among the composers who took advantage of the theme’s endlessly rich musical possibilities. Later composers also paid homage to La Folia. It surfaces briefly at this moment in the second movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Franz Liszt included it in his La Rhapsodie espagnole. Even contemporary Welsh composer Karl Jenkins (of “diamond commercial” fame) has written his own La Folia variations for marimba and strings.

One of the most famous Baroque versions of La Folia was Arcangelo Corelli’s. In a 2013 Listeners’ Club post we explored a few contrasting performances of this music. Shinichi Suzuki’s La Folia in the opening of Suzuki Violin Book 6 is based loosely on Corelli’s piece.

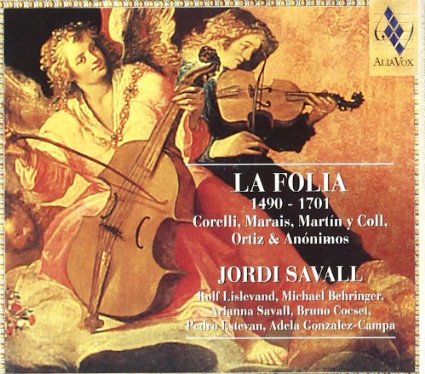

Recently, I ran across another great La Folia performed by Spanish viola da gamba player Jordi Savall. No one is sure who wrote this piece. It is part of a collection of now anonymous music called Flores de Música (“Musical Flowers”), compiled by Spanish organist and composer Antonio Martín y Coll (died c. 1734). The viola da gamba is a stringed instrument which first appeared in Spain in the mid to late fifteenth century. You’ll notice a distinctly Spanish flavor in the instrumentation (castanets and the wood of the bow hitting the strings) and rhythm (1:04, for example). Listen closely to the way the guitar’s dance-like rhythm livens things up at 5:17.

At their best, theme and variations are about fun-loving virtuosity and a wide range of expression and drama. These aspects are on full display here:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Rachmaninov’s Variations on a Theme of Corelli

Now, let’s hear Sergei Rachmaninov’s 1931 Variations on a Theme of Corelli, Op. 42. Throughout twenty ferocious variations and a coda, the La Folia theme enters bold and adventurous new territory. Following the opening statement of the theme, the music begins quickly to move far afield harmonically. There’s a spirit of the “trickster” here as we’re thrown sudden curveballs (1:08). At the same time, it’s easy to sense something ominous and slightly gloomy under the surface. At moments we get the faintest glimpse of the outlines of the Dies Irae (the Latin “Day of Wrath” chant) which shows up in so much of Rachmaninov’s music. Listen for the ghoulish low notes around the 4:44 mark. As the final, solemn chord dies away, ghosts evaporate.

This work is dedicated to the violinist Fritz Kreisler, with whom Rachmaninov performed occasionally. Rachmaninov never recorded this piece. In a letter dated December 21, 1931 he lamented:

I’ve played the Variations about fifteen times, but of these fifteen performances only one was good. The others were sloppy. I can’t play my own compositions! And it’s so boring! Not once have I played these all in continuity. I was guided by the coughing of the audience. Whenever the coughing would increase, I would skip the next variation. Whenever there was no coughing, I would play them in proper order. In one concert, I don’t remember where – some small town – the coughing was so violent that I played only ten variations (out of 20). My best record was set in New York, where I played 18 variations. However, I hope that you will play all of them, and won’t “cough”.

You won’t hear any coughing or miss any skipped variations in Hélène Grimaud’s excellent 2001 recording:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iq7MmZv2ASU

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]