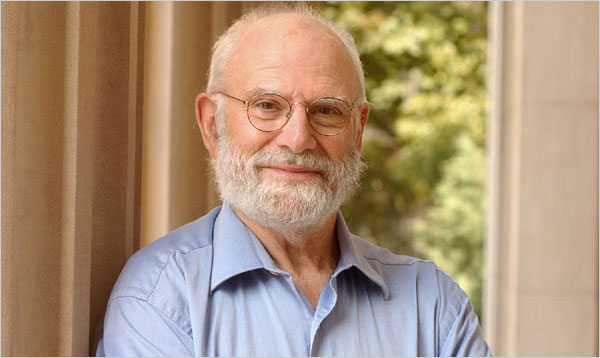

The English neurologist Oliver Sacks passed away yesterday at the age of 82, following a battle with cancer. Sacks examined the relationship between music and the brain. His research highlighted the surprising ways some Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s patients respond to music. Demonstrating that music occupies more areas of the brain than language, Sacks considered music to be fundamental to humanity. His findings are outlined in his 2007 book, Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain and the NOVA documentary, Musical Minds.

In an interview, Oliver Sacks once talked about his first musical memory. He recalls his brother playing C.P.E Bach’s Solfegietto:

That piece of music was banged into my memory. It’s a piano piece with a very Bach fugal structure. It’s formally intricate, but it also arouses an intense emotion that I can’t really describe. I think it was a rather jolly piece. But my brother died a couple years ago, and now it comes to me as if it were his signature tune, with an elegiac quality.

Oliver Sacks’ contributions, seemingly driven by a passion and fascination for music, were significant. His use of music to unlock the otherwise bleak world of patients with neurological disorders was inspiring. He attempted to give us a glimpse “under the hood” in an effort to capture the essence of our relationship with a piece of music. But reading Sachs’ description of Solfegietto, it’s easy to sense that, despite his extensive research, the true power and meaning of music remains elusive. Beyond the reach of science, it “can’t really be described.” W.H. Auden’s words come to mind:

We are lived by powers we pretend to understand.

Here is C.P.E Bach’s Solfeggio, performed by the Israeli pianist, Tzvi Erez. Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788) was the second surviving son of J.S. Bach.

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find C.P.E Bach’s Solfeggio at iTunes, Amazon.

- Find Oliver Sacks’ books.

- Watch this discussion.

- Quotes about music

[/unordered_list]