When you think of ambient concert music that conjures up vast sonic landscapes, the name John Luther Adams may come to mind. Adams, an American composer and longtime resident of Alaska, was awarded the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Music for his orchestral work, Become Ocean, premiered by conductor Ludovic Morlot and the Seattle Symphony in June, 2013. It’s music which unfolds slowly in rich, colorful waves of sound, evoking the eternal power, depth and cool darkness of the awesome bodies of water which cover seventy-one percent of Earth’s surface.

But Adams wasn’t the first composer to create an ambient sonic portrait of the sea. Listen to Jean Sibelius’ tone poem, The Oceanides, Op. 73, and you’ll get a similar sense of murky depths and mythological “Nymphs of the Waves” (the loose translation of the Finnish title, Aallottaret).

The Oceanides emerges from the depths of the orchestra, as rising and falling string lines wander in a daze. Flutes provide a playful splash of color. The dreamy serenity of the flutes’ opening motives would be at home in any hazy New-age composition. And while the motives develop (certainly at a faster clip than in the static Become Ocean), we are left with a feeling of the circular and timeless. In this excerpt, listen to the way the horns resolve, only to quickly move back to unsettled dominant territory and then dissolve into something new.

At moments, there are hints of that other piece about the ocean, Claude Debussy’s La mer, completed eight years earlier in 1905. But beyond a few passing similarities, Sibelius’ tone poem feels different than La mer. As with Sibelius’ symphonies, the music spins forward and develops, yet we quickly realize that there is no ultimate goal, just another icy, slowly changing landscape over an endless horizon. That’s the feeling we get from the long, endless series of waves in Become Ocean. The Oceanides has one climactic moment of resolution that feels strangely similar to the crest of one of Become Ocean‘s sonic waves. From there, the music falls back and we’re left with the unending expanse of the ocean.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CcMMI2ws2Ss

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

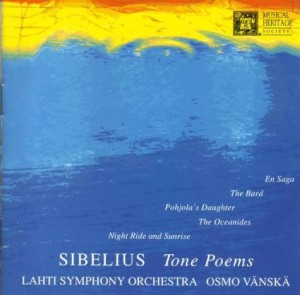

- Find Osmo Vänskä’s recording of The Oceanides with the Lahti Symphony Orchestra (featured above) at iTunes, Amazon.

- The Oceanides underwent a series of revisions. Hear one of Sibelius’ earlier versions, set a half step lower in the key of D-flat.

- Find John Luther Adams’ Become Ocean at iTunes, Amazon.

- Browse the Listeners’ Club archive and find other posts featuring Sibelius’ music.

[/unordered_list]