Yesterday was the seventieth anniversary of the allied liberation of Auschwitz at the end of the Second World War. Orchestras around the world, including the Richmond Symphony, commemorated the event by playing often neglected music by Jewish composers who were affected by Nazi atrocities.

Music was performed frequently in the concentration camps. At Terezin, near Prague, prisoners defiantly performed Verdi’s Requiem sixteen times as a veiled condemnation of the Nazis. The conductor Raphael Schächter taught his fellow prisoners the music by rote, using a single score. As prisoners were moved to other camps, Schächter painstakingly began the process again.

In 1936, Jewish Polish violinist Bronislaw Huberman founded the Palestine Symphony Orchestra (now the Israel Philharmonic). Huberman helped nearly 1,000 Jewish musicians flee the Third Reich. He is often credited with helping to preserve the Jewish musical tradition.

Violins of Hope by James A. Grymes examines the importance of the violin in Jewish culture.

Erwin Schulhoff’s String Quartet No. 1

Czech composer Erwin Schulhoff (b. 1894-1942) was mentored by Antonín Dvořák and later studied with Claude Debussy. You can hear both Czech folk music and the wispy sounds of Impressionism in his brief but powerful String Quartet No. 1. Schulhoff died of tuberculosis at the Wülzburg concentration camp on August 18, 1942.

This piece contains ghostly and ethereal voices. Listen to the way the final movement fades into eternity.

Here is a performance by the Kocian Quartet:

[ordered_list style=”decimal”]

- Presto con fuoco (0:00)

- Allegretto con moto e con malinconia grotesca (2:15)

- Allegro giocoso alla Slovacca (5:53)

- Andante molto sostenuto (8:50)

[/ordered_list]

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Korngold and the “Hollywood Sound”

We thought of ourselves as Viennese; Hitler made us Jewish.

-Erich Wolfgang Korngold

In one of the great ironies of music history, Hitler was partly responsible for the lush, colorful sound we associate with the golden age of Hollywood film scores. Jewish composers, including Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Max Steiner, Dimitri Tiomkin, and Miklós Rózsa emigrated to the United States as the film industry was blossoming. Had these composers been free to remain in Europe, many of the greatest film scores would likely have become symphonies.

Korngold created film scores for movies like The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), The Sea Hawk (1940), and Kings Row (1941). The later score seems to have subconsciously (or consciously) influenced the Main Theme of John Williams’ Star Wars as well as Superman. Listen to a suite from the score and then a back-to-back comparison of the two themes here. This music can be heard as a continuation of the late Romantic tradition of Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss. In the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Brendan G. Carroll writes,

Treating each film as an ‘opera without singing’ (each character has his or her own leitmotif) [Korngold] created intensely romantic, richly melodic and contrapuntally intricate scores, the best of which are a cinematic paradigm for the tone poems of Richard Strauss and Franz Liszt. He intended that, when divorced from the moving image, these scores could stand alone in the concert hall. His style exerted a profound influence on modern film music.

Korngold’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35, written in 1945, draws on music from the movies Anthony Adverse (1936), Another Dawn (1937), The Prince and the Pauper (1937), and Juarez (1939). The concerto was dedicated to Alma Mahler, the widow of Gustav Mahler, who served as a childhood mentor to Korngold. There are moments where the spirit of late Mahler briefly surfaces (in the first movement at 6:44 in the recording below). Jascha Heifetz gave the premiere with the Saint Louis Symphony in 1947.

Some concertos open with a long orchestra introduction before the solo instrument is heard. By contrast, in this concerto the violin greets us from the start; the expansive, open intervals of the theme suggesting endless possibilities. Waves of colorful sound leap from every corner of the orchestra throughout the outer movements. At moments, the violin becomes a solitary voice, venturing towards the wilderness of atonality before the orchestra pulls us back.

The Romanza enters intimate new territory. Listen carefully to the subtle conflict in the second movement’s opening chord. This is an instance where one note changes everything. The music seems to be searching. We hear high, shimmering voices followed by a dark and icy low chord. Notice the splashes of color which sparkle around the violin’s lamenting melody.

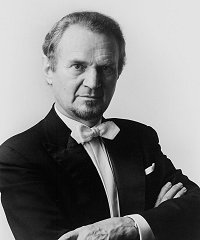

Here is a performance by Hilary Hahn and the Kölner Philharmonie, conducted by Heinrich Schiff. Hahn talks about the music here.

[ordered_list style=”decimal”]

- Moderato nobile (0:00)

- Romanze (8:36)

- Allegro assai vivace (16:44)

[/ordered_list]

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]