Listening to Robert Schumann’s Fantasiestücke, Op. 73 forces us to live in and enjoy the moment. The three short “Fantasy Pieces,” written in just over two days in February, 1849, are filled with abrupt, slightly schizophrenic, changes in mood. Moments of deep introspection, followed by bursts of euphoria, remind us of Florestan and Eusebius, the split personalities which inhabit much of Schumann’s music. In the Fantasy Pieces, each delightful and unexpected harmonic shift whisks us off to a new, distant world of expression. (Listen to the chord at 1:40 in the first clip, below, for example). These stream of consciousness “songs without words” develop through obsessively repeated musical fragments which toss and turn as they search for an ultimate resolution. The recurring opening motive in the last movement grabs our attention and then pauses, leaving us hanging. Listen for the moment towards the end where we get a sudden, sly resolution (9:58).

Listening to Robert Schumann’s Fantasiestücke, Op. 73 forces us to live in and enjoy the moment. The three short “Fantasy Pieces,” written in just over two days in February, 1849, are filled with abrupt, slightly schizophrenic, changes in mood. Moments of deep introspection, followed by bursts of euphoria, remind us of Florestan and Eusebius, the split personalities which inhabit much of Schumann’s music. In the Fantasy Pieces, each delightful and unexpected harmonic shift whisks us off to a new, distant world of expression. (Listen to the chord at 1:40 in the first clip, below, for example). These stream of consciousness “songs without words” develop through obsessively repeated musical fragments which toss and turn as they search for an ultimate resolution. The recurring opening motive in the last movement grabs our attention and then pauses, leaving us hanging. Listen for the moment towards the end where we get a sudden, sly resolution (9:58).

Schumann originally wrote this music for the clarinet, but his version for cello is equally interesting. In both versions there’s a strong sense of musical conversation between the piano and the other instruments. At moments (such as the passionate dialogue between the cello and piano at 6:50) you may be reminded of the musical link between Schumann and Brahms.

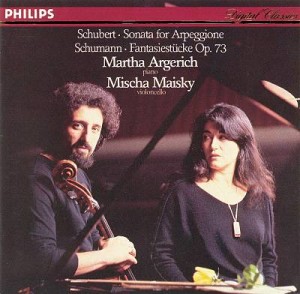

Here is cellist Mischa Maisky and pianist Martha Argerich:

…and here is the version for clarinet, featuring Martin Fröst and Jonathan Biss. Consider the ways the piece changes with each instrument.

Listen to the second and third movements.

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find the Mischa Maisky/Martha Argerich recording at iTunes, Amazon.

- Find the Martin Fröst/Jonathan Biss recording at Amazon.

[/unordered_list]