Clumsy…badly written…vulgar…with only two or three pages worth preserving.

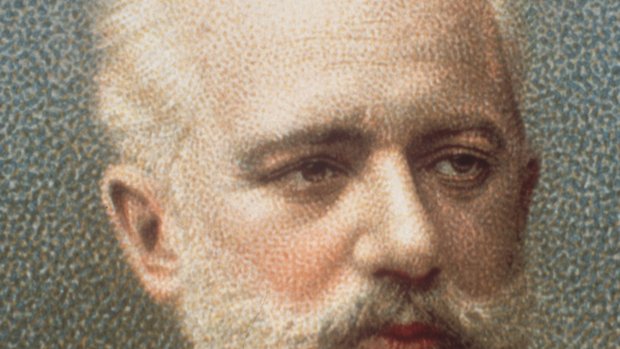

That was the harsh assessment of Tchaikovsky’s friend, the pianist Nikolai Rubinstein, following a private reading of the Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor, Op. 23 on Christmas Eve, 1874. Rubinstein went on to call the piece “worthless” and “impossible to play.” But Tchaikovsky refused to “alter a single note” (he later made a few revisions in 1879 and 1888) and the concerto now joins a long list of beloved war horses prematurely deemed “unplayable.” The violinist Leopold Auer had a similar, if slightly less devastating reaction to the Violin Concerto.

Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto breaks the rules. It opens with an unabashedly expansive melody in the “wrong” key of D-flat major. Beyond the first movement’s introduction, this powerful theme isn’t heard again, but it opens the door for all that follows. As Kenneth Woods points out, the concerto develops from motivic cells present in this memorable opening “seed.”

In the second movement, a series of instrumental voices, each with its distinct persona, contributes to the musical conversation. First we hear the solitary flute against the backdrop of spare pizzicati. We step into a warm new world with the first statement of the piano. Listen to the velvety descending string line and the bassoon in the background. Before the movement is over, the oboe, horn, and cello have contributed to the conversation.

One of my favorite moments in this concerto comes at the end of the final movement (beginning around 38:20, below), as our sense of expectation is stretched almost to its breaking point. As the bass and tympani hold a dominant pedal, the violins search for the theme we know is coming (38:38). At 39:31 the final notes of the piano’s dramatic cadenza seem to be leading a clear tonic resolution. Another composer might have given us that clear downbeat resolution. But, because of the harmony of Tchaikovsky’s theme (beginning on the dominant), the triumphant orchestral tutti begins and for a split second we’re still hanging on the dominate.

Here is pianist Evgeny Kissin with Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic on New Years Eve, 1988:

[ordered_list style=”decimal”]

- Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso — Allegro con spirito 0:00

- Andantino semplice — Prestissimo 24:40

- Allegro con fuoco 33:18

[/ordered_list]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kzoPBj5NKRg

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

Additional Listening

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- a younger Martha Argerich and then another performance from a few years later. At the end of the second performance the audience and conductor Charles Dutoit urge a clearly annoyed Argerich to play an encore and she gives in with a magical performance of Schumann.

- Eugene Istomin with the Philadelphia Orchestra

[/unordered_list]