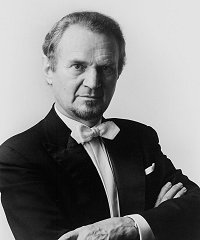

Polish-born conductor Jerzy Semkow passed away last week at the age of 86. A longtime French citizen who resided in Paris, Semkow served as principal conductor of the National Opera in Warsaw (1959-1962), the Royal Danish Opera and Orchestra in Copenhagen (1966 to 1976), and as Music Director of the Orchestra of Radio-Televisione Italiana (RAI) in Rome. Between 1975 and 1979 he was Music Director of the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra. Semkow enjoyed long associations as a regular guest conductor with American orchestras, including the Detroit Symphony and the Rochester Philharmonic. His mentors included Erich Kleiber, Bruno Walter and Tullio Serafin.

As a teenager, I heard the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra perform numerous times under Jerzy Semkow. His concerts left a powerful and lasting impression. Even after many years, I can still vividly recall the music which was performed on each program. His interpretations of Mahler and Bruckner seemed to come alive with an almost supernatural power. He brought a unique warmth and purity to Mozart. It’s likely that he left a subtle imprint on the sound and musicianship of the orchestra which remained beyond his guest conducting appearances.

Audience members and musicians will remember Jerzy Semkow’s slightly eccentric and aristocratic stage presence. Following the orchestra’s tuning, minutes would often elapse before Semkow appeared onstage, wielding his enormously long baton. During the final applause for a large orchestral work, he would often walk throughout the orchestra, acknowledging each section.

Semkow’s deep and inspiring musical vision became apparent in rehearsals. On one occasion, the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra offered a solid first reading of the opening of the final movement of Brahms’ Second Symphony, a hushed passage which requires great control. Semkow called attention to the first note, which he found to be lacking in warmth and buoyancy. Immediately, the sound of the orchestra was transformed and the entire movement took shape.

The Detroit Free Press offers this tribute. Also, read comments by Leonard Slatkin, William Wolfram, Peter Donohoe and others at Norman Lebrecht’s Slipped Disc. Submit your own memories of Jerzy Semkow in the comment thread below.

Highlights from Jerzy Semkow’s Recordings

Schumann’s Third Symphony “Rhenish” performed by the Saint Louis Symphony:

Listen to the second, third, fourth and fifth movements.

Here is a live 1978 performance of Brahms’ Second Piano Concerto with pianist Jorge Bolet and the Cleveland Orchestra:

Listen to the second, third and fourth movements.

A complete recording of Borodin’s opera, Prince Igor with the National Opera Theatre of Sofia:

A young Jerzy Semkow accompanies legendary French violinist Zino Francescatti in Mozart’s Fourth Violin Concerto:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FZ5jvT3cXTk

The music of Russian romantic composer Alexander Borodin (1833-1887) is filled with stunningly beautiful melodies. One example can be heard in the third movement (Nocturne) of Borodin’s String Quartet No. 2. Let’s listen to a recording by the Emerson String Quartet. Consider the unique personality of each voice of the string quartet and notice the way the voices interact, creating a musical conversation. Pay attention to harmony and inner voices. Each time the melody returns, Borodin puts it in a slightly different harmonic package:

The music of Russian romantic composer Alexander Borodin (1833-1887) is filled with stunningly beautiful melodies. One example can be heard in the third movement (Nocturne) of Borodin’s String Quartet No. 2. Let’s listen to a recording by the Emerson String Quartet. Consider the unique personality of each voice of the string quartet and notice the way the voices interact, creating a musical conversation. Pay attention to harmony and inner voices. Each time the melody returns, Borodin puts it in a slightly different harmonic package: