Gustav Mahler described the opening of the First Symphony as “Nature’s awakening from the long sleep of winter.” A seven octave deep “A” emerges out of silence, slipping into our consciousness on the level of pure sound. The high harmonics in the violins seem as natural and fundamental as the white noise of insects in a forest. The motive, which forms the bedrock of the symphony, slowly, searchingly takes shape in the woodwinds. As the music progresses, we hear bird songs and the echoes of distant fanfares in the clarinets and offstage trumpets.

Mahler’s music speaks to us on a deeply psychological level, evoking complex, indescribable emotions. It embodies heroic struggle and can alternate between moments of transcendence and the vulgar street sounds of a bohemian village band. Mahler said, “A symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything.” The sense of paradox in Mahler’s music is captured in a story of Mahler as a child, frequently running into the street to escape his father’s violent abuse of his mother, and suddenly being met with the cheerful sounds of an organ grinder.

The First Symphony grew out of Mahler’s song cycle, Songs of a Wayfarer. It was originally conceived as a five movement symphonic poem. Mahler later cut the second movement, Blumine, and dropped the subtitle, “The Titan”, which was a reference to a novel by Jean Paul. The piece requires a greatly expanded orchestra (seven horns, four trumpets, four trombones, tuba and an expanded woodwind and percussion section). At times, instruments are used in strange new ways, playing out of their normal range to create mocking, demonic sounds. In the second movement we hear the distinctive, raspy sound of stopped horns.

Mahler was a prominent conductor (and champion of Wagner’s operas) and his scores were meticulously marked with words and phrases intended to guide future interpreters. Common musical themes reappear throughout Mahler’s nine symphonies and in some ways these works can be heard as one massive symphony. The bewilderment of the audience at the 1889 premier in Budapest is a testament to the revolutionary nature of Mahler’s vision. The music would come to be embraced by audiences of the twentieth century. Today, performances of Mahler’s symphonies are often the dramatic high point of an orchestra’s season.

Here is Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 in D Major, performed by conductor Pierre Boulez and the Chicago Symphony. Listen carefully to the distinct voices of the instruments (for example the horns at 10:44). What personas do they suggest? How does the final movement resolve the symphony as a whole?

- Langsam. Schleppend 00:00

- Kraftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell 16:00

- Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen 22:48

- Sturmisch bewegt 33:28

Did you feel a sense of growing anticipation in the first movement? Go back and listen to the opening with those sustained “A’s” (the dominant in D major). It isn’t until around 4:06 that the music settles into a resolution in D major. We can relax and breathe easily. But at 7:59 we’re back where we started in the opening and this time it’s more ominous. All of the raw energy and tension, which has been building from the beginning, is released in one frighteningly explosive, but ultimately heroic climax towards the end of the movement (14:18). We’re left with crazy, giddy humor and a musical cat and mouse game in the final bars.

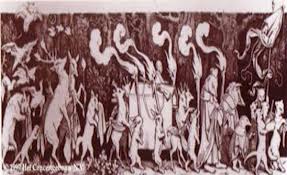

The third movement was inspired by a children’s wood carving, The Huntsman’s Funeral, in which a torch-lit procession of animals carry the body of the dead huntsman. At the end of the movement, the sounds of the procession fade into the distance. You probably recognized the folk melody, Frère Jacques. Here it’s transformed into minor and played by the double bass, an instrument rarely featured in orchestral solos. Consider the persona of the double bass sound. The bizarre interjections of Jewish band music give this movement its ultimate sense of paradox and irony.

Opening amid a life and death struggle and ending in triumph, the final movement forms the climax of the symphony. Amid birdcalls, the bassoon recaps a familiar fragment (45:23) and for a moment we hear echoes of the first movement. The haunting motive from the opening of the first movement is transformed into a heroic proclamation in major. You may hear a slight, probably unconscious, similarity to Handel’s equally triumphant Hallelujah Chorus from Messiah. In the score, Mahler asks the seven horns to stand for the final statement of the theme, “so as to drown out everything…even the trumpets.”

For some interesting links, watch Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concert, Who is Gustav Mahler? and Keeping Score with Michael Tilson Thomas.

Recordings, old and new

There are many great recordings of this piece. Here are a few which I recommend. Share your favorites in the thread below.

- Marin Alsop and the Baltimore Symphony I’ve been listening to this 2012 Naxos release a lot recently. The recording captures the dark, blended warmth of the Baltimore brass section in Meyerhoff Hall. The bass solo in the third movement is transformed into a tutti. The brisk tempo at end of the final movement suggests a youthful energy. Alsop talks about the piece here.

- Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra This 1969 recording is interesting because it includes the Blumine movement which Mahler cut. The lush, velvety Philadelphia string sound is on display. Listen here.

- Kurt Masur and the New York Philharmonic At the end of his life, Mahler served as the New York Philharmonic’s music director. Mahler is in the orchestra’s DNA.

- Leonard Bernstein and the Concertgebouw Orchestra Bernstein was influential in promoting Mahler’s music around the world in the mid-twentieth century. Listen here.

- Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony MTT recorded all of the Mahler Symphonies in San Francisco. The recordings are taken from live concerts. Listen here.

- Pierre Boulez and the Chicago Symphony This is the recording featured above.