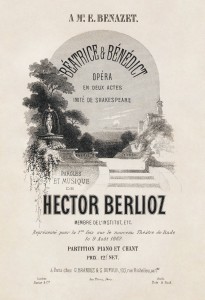

Béatrice et Bénédict, Hector Berlioz’s two act opéra comique adaptation of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, isn’t exactly a staple of the modern opera repertoire. It gets occasional performances, but is commonly overshadowed by more famous Shakespeare-based operas: Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth, Otello, and Falstaff, and Benjamin Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Béatrice et Bénédict, Hector Berlioz’s two act opéra comique adaptation of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, isn’t exactly a staple of the modern opera repertoire. It gets occasional performances, but is commonly overshadowed by more famous Shakespeare-based operas: Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth, Otello, and Falstaff, and Benjamin Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

But Béatrice et Bénédict was a smash hit when it premiered at the the Theater der Stadt in the German spa town of Baden-Baden on August 9, 1862. Berlioz referred to the opera as “A caprice written with the point of a needle.” Its sparkling score comes to life with a uniquely vivacious energy. At the same time, the forward motion of the plot occasionally gives way to atmospheric moments of serene, otherworldly beauty. Berlioz biographer David Cairns writes, “Listening to the score’s exuberant gaiety, only momentarily touched by sadness, one would never guess that its composer was in pain when he wrote it and impatient for death.”

The opera’s libretto, written by Berlioz, simplifies Shakespeare’s play, eliminating subplots in order to emphasize the relationship between the title characters. As the first act opens, the citizens of the Sicilian town of Messina have gathered to welcome home the victorious army of Don Pedro of Aragon, following a successful battle campaign against the Moors. Héro eagerly awaits the return of her fiancé, Claudio. Meanwhile, Béatrice greets the returning Bénédict in a strikingly different way. The two take great pleasure in trading insults, masking their mutual attraction. In the opening of Berlioz’s Overture we can hear the couple playfully hurtling verbal barbs at one another. It’s a musical cat and mouse game which is constantly throwing us witty curve balls. We hear this “needling” opening motive throughout the overture, sometimes as teasing and taunting background interjections (listen around 4:12 and 6:13). The music which follows suggests the farcical trickery of the plot, which includes “accidentally” overheard conversations. But we also get a sense of the supernatural lurking underneath…the mystery and eternal beauty of a still summer night and a hint of Nuit paisible et serene! (“Peaceful and Good Night!”), the nocturne duet which concludes the first act.

Here is Colin Davis’ 2005 recording with the Dresden Staatskapelle:

Kathleen Battle battle sings Je vais le voir, Héro’s quietly majestic aria from the opening of the first act. Héro awaits the return of Claudio, their marriage and their trouble-free life ahead:

Sylvia McNair and Catherine Robbin sing Nuit paisible et serene! (“Peaceful and Good Night!”), the nocturnal duet of Héro and Ursule at the end of the first act. The duet embodies a “French sound” which seems to subtly anticipate everything from Léo Delibes’ Flower Duet from Lakme (1883) to Gabriel Faure’s Pavane, Op. 50 (1887).

Human follies evaporate as Héro and Ursule comment on the serene, moonlit night, the faint hum of insects in a nearby meadow, and the gentle sound of wind rustling through the trees. From the brief opening recitative, which strangely suggests the vocal purity of baroque opera, Berlioz’ orchestration draws us into the stillness of the night. As the curtain falls on Act 1, the music fades into the night…

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find Colin Davis’ recording of the Béatrice et Bénédict Overture with the Dresden Staatskapelle at iTunes, Amazon.

- Find Kathleen Battle’s recording, French Opera Arias at iTunes, Amazon

- The third clip, featuring Sylvia McNair and Catherine Robbin comes from a recording of the entire opera with John Nelson conducting Opéra de Lyon. Find at Amazon.

[/unordered_list]