The music of Beethoven is opening orchestra seasons on both coasts this month.

Next week, the Los Angeles Philharmonic will offer an all-Beethoven concert gala. It’s the first in a series of concerts called Immortal Beethoven, in which all nine Beethoven symphonies will be performed between September 29 and October 11, along with chamber music and children’s programs. The LA Phil has even launched this virtual reality tour experience, cleverly called “Van Beethoven,” which takes the music into the community. A downloadable app makes it available to music lovers everywhere.

But first, on Thursday the New York Philharmonic’s season kicks off with the Grieg Piano Concerto, performed by Lang Lang and Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, conducted by Music Director Alan Gilbert. The concert will be broadcast on PBS at 9:00 on September 24.

Written between 1811 and 1812 while Beethoven recovered in the Bohemian spa town of Teplice, the Seventh Symphony is a simultaneously ferocious and benevolent animal. It snarls and growls with revolutionary, Romantic fervor. It’s buoyant and fun-loving, with a hint of something slightly terrifying lurking under the surface. The first movement opens with mighty chords- the musical equivalent of massive architectural columns. In between these opening chords, voices gradually emerge and join together. As the movement progresses, it’s easy to sense the music evolving and developing like a quickly growing vine.

The second movement is built on a solemn rhythmic ostinato. It begins as a quiet drumbeat. As we move into a second theme, sliding into major, the drumbeat is still there in the pizzicato, insistent and unrelenting. By the end of the movement, it has grown into a terrifying, all-consuming giant.

The third movement gives us a hint of bubbly Rossini, interspersed with a noble trio section. The fourth movement explodes with ferocious energy (one of the few times Beethoven uses the loudest possible dynamic marking, fff). It moves suddenly from one unexpected key to another. There’s a sense of upward lift, and by the conclusion of the movement we have a strange feeling of transcendence.

British composer, pianist, conductor and commentator Antony Hopkins described Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony this way:

The Seventh Symphony perhaps more than any of the others gives us a feeling of true spontaneity; the notes seem to fly off the page as we are borne along on a floodtide of inspired invention. Beethoven himself spoke of it fondly as “one of my best works”. Who are we to dispute his judgment?

[hr]

As the New York Philharmonic prepares to play Beethoven’s Seventh this week, let’s explore five landmark performances from the Philharmonic’s past. These clips, spanning forty years, will give you a sense of how the piece can change depending on the conductor, as well as how the orchestra’s playing has evolved:

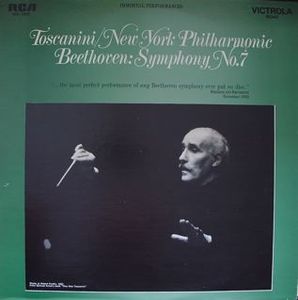

Arturo Toscanini, 1936

Here is the first movement from Arturo Toscanini’s 78rpm/Victor recording, made on April 9 and 10, 1936. (This scratchy, at times barely audible, 1933 live concert recording of the first and last movements is also worth hearing. In 1931, under Toscanini’s leadership, the New York Philharmonic became the first orchestra in the country to offer regular live radio broadcasts). Toscanini, who debuted with the New York Philharmonic in 1926, served as music director between 1928 and 1936. He was noted for the laser beam precision of his baton technique.

According to the New York Philharmonic’s website,

In 1930, Toscanini led the Philharmonic on a highly successful tour of Europe. The following year, he was attacked and beaten while in Italy for his refusal to play the Fascist anthem, and he later made public his opposition to Nazi persecution of the Jews. Many saw in Toscanini’s Beethoven cycle with the New York Philharmonic during the 1932-33 season a musical repudiation of tyranny that matched his public opposition to Hitler.

Artur Rodzinski, 1946

Artur Rodzinski was the Philharmonic’s music director 1943 to 1947, succeeding English conductor Sir John Barbirolli. Rodzinski was considered to be an “orchestra builder,” shaping a clean, modern sound:

Bruno Walter, 1951

German-born conductor Bruno Walter turned down an offer to become the New York Philharmonic’s music director in 1942. In 1947, following the resignation of Artur Rodzinski, Walter briefly accepted the position until 1949, but changed his title to “Music Advisor.” In this clip you can hear him rehearsing the first movement of Beethoven’s Seventh, emphasizing the buoyant dance-like rhythm.

Leonard Bernstein, 1958

Leonard Bernstein was music director of the New York Philharmonic from 1958 to 1969, and served as Laureate Conductor until his death in 1990. As a young assistant conductor, he rose to prominence after stepping in as a substitute for Bruno Walter with only a few hours’ notice. Bernstein made two recordings of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony with the Philharmonic. This is the first:

Pierre Boulez, 1975

Pierre Boulez succeeded Leonard Bernstein as music director, serving form 1971 to 1977. This clip from a live concert doesn’t have the best audio quality, but Boulez’ interpretation is worth hearing:

[hr]

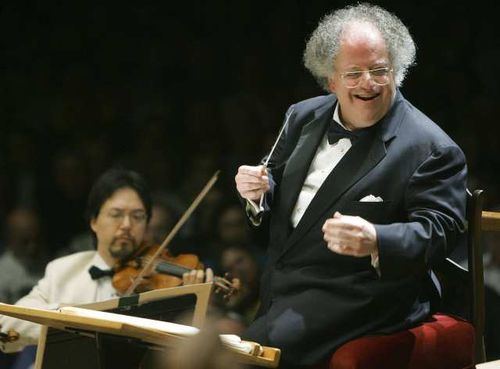

…and here’s a taste of what you’ll hear on Thursday: the current New York Philharmonic, conducted by Alan Gilbert:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find Toscanini’s recording at Amazon.

- Find Walter’s recording at Amazon.

- Find Bernstein’s 1968 recording at iTunes, Amazon.

[/unordered_list]