In the clip below, conductor Mariss Jansons leads the Berlin Philharmonic in a spectacular and rousing performance of the overture to the opera Oberon by Carl Maria von Weber.

Weber’s music contains some of the earliest seeds of Romanticism. His orchestration was new and innovative. It mixed tonal colors in exciting ways and expanded the size and power of the orchestra. (Notice the trombones, which were a relatively new addition at the time). Berlioz referred to Weber in his influential Treatise on Instrumentation and Debussy remarked that the sound of Weber’s orchestra was “obtained through the scrutiny of the soul of each instrument.” Weber’s opera Euryanthe anticipated Wagner’s Leitmotif technique, in which a short, recurring musical phrase is used to represent a character or idea. Even twentieth century composers returned to Weber’s music. (Listen to Paul Hindemith’s Symphonic Metamorphosis, which is based on themes by Weber).

The Oberon Overture begins with a distant horn call and slowly awakening strings. Listen to the harmony at 1:15 and you’ll be reminded of yet-to-be-written Wagner. A few moments later at 1:33, we hear the playful laughter of Richard Strauss’ Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks. And then, after this sleepy and introspective opening, the music suddenly explodes into a fireball of virtuosity. A cast of characters comes alive through the instruments of the orchestra. The overture, which began so quietly, ends in a high-flying flourish of euphoria.

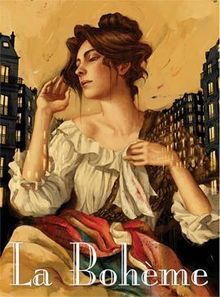

Oberon was first performed at London’s Covent Garden on April 12, 1826. The three act Romantic opera’s plot dates back to a medieval French story, Huon of Bordeaux. You can hear Maria Callas sing an excerpt from the opera here.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3lz0Fo-Blus

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]