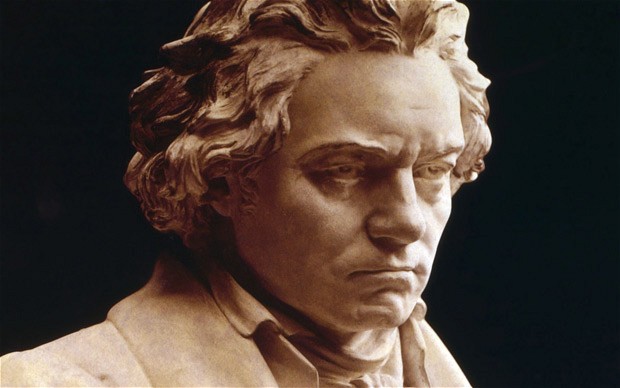

Beethoven inscribed the transcendent third movement of his Op. 132 String Quartet with the descriptive title, “Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der lydischen Tonart” (Holy song of thanksgiving of a convalescent to the Deity, in the Lydian Mode). The words reflected Beethoven’s gratitude for a burst of renewed health, following a near-fatal stomach ailment during the winter of 1824-25. They are the words of a composer who, earlier in life, grappled with the devastating realities of hearing loss, and ultimately triumphed.

Written in the final two years of Beethoven’s life, following the completion of the Ninth Symphony, the String Quartet No. 15, Op. 132 enters the strange, mysterious world of Beethoven’s “late string quartets.” These works were so groundbreaking and radical that they left audiences baffled when they were first performed. The violinist and composer Louis Spohr called these quartets “indecipherable, uncorrected horrors.” Another musician said, “we know there is something there, but we do not know what it is.” After hearing the Op. 131 Quartet, Franz Schubert remarked, “After this, what is left for us to write?” In the twentieth century, Igor Stravinsky called the Große Fuge, Op. 133 “an absolutely contemporary piece of music that will be contemporary forever.” Even Beethoven seems to have understood the power of these musical revelations. Writing in English to a friend in 1810 regarding the String Quartet No. 11 in F minor (“Serioso”), Op. 95 he said, “The quartet is written for a small circle of connoisseurs and is never to be performed in public.” It would be easy to call Beethoven’s late string quartets “ahead of their time.” In fact, they seem eternally timeless. Listening to this music, you don’t get any sense of style or historical period. They become music in its purest form.

The “Holy song of thanksgiving” is the longest movement in the Op. 132 Quartet and comes at the heart of the five-movement work. The overlapping voices in the opening can be heard as a reference to the ghostly opening of the Quartet’s first movement. Throughout the third movement, the music alternates between the opening chorale (in modal F) and a slightly faster section in D major, which Beethoven marks, “with renewed strength.” Each time the D major section returns, it becomes more embellished, joyful and frolicking (listen to the sense of breathlessness in this passage). By contrast, the opening chorale becomes increasingly introverted. Toward the end of the movement, the music fades into open fifths (a sound which emerges out of silence in the opening of the Ninth Symphony). The final moments of the third movement reach for an ultimate climax and then fall back into tender acceptance. As the chorale returns one last time, giving each voice of the quartet a final statement, we sense that the music is trying to hang on, as if afraid to let go. When we reach the end, the final chord in F feels strangely unresolved, overpowered by the preceding passage’s convincing pull to C major. Beethoven’s “Holy song of Thanksgiving” moves beyond conventional key relationships, making us focus on the moment, rather than a far-off goal, and leaving us with a sense of the circular and eternal.

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find the Takacs Quartet’s recording at iTunes, Amazon.

- Hear the complete Op. 132 Quartet.

- Beethoven’s Op. 132 may have inspired T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets.

[/unordered_list]