In June the Metropolitan Museum of Art and St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary hosted a thought-provoking discussion, Spirit in Sound and Space- A Conversation Inspired by Arvo Pärt, in conjunction with this summer’s Arvo Pärt Project. The discussion brought together architect Steven Holl, neuroscientist Robert Zatorre, and musician and theology professor Peter Bouteneff.

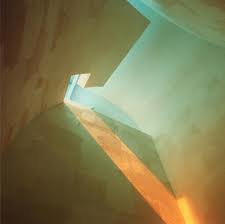

For Steven Holl, one of the most visionary contemporary architects, ideas often emerge through the process of painting watercolors. Buildings like the Chapel of St. Ignatius in Seattle and the Knut Hamsun Center, two hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle in Hamarøy, Norway, register the flow of time with constant, subtly changing plays of light and shadow. Holl notes that Arvo Pärt “sees sound as space.”

“Music surrounds you. It’s an immersive experience” says Holl, whose work is influenced by music. “Architecture, space surrounds you.”

Zatorre points out that the parietal lobe of the brain handles our perception of music as well as space. His insights, based on a strictly mechanistic view of the workings of the brain, are interesting, but in the end they leave many questions unanswered. The “spirit” part of the conversation remains elusive. What is the source of a creative idea? How do great buildings suddenly emerge out of Steven Holl’s brushstrokes? Albert Einstein hinted at these questions when he said,

The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and all science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed.

A new voice emerges…

The story of Estonian composer Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) demonstrates the mysteries of the creative process. At the end of the 1960s, Pärt suddenly abandoned the dissonant, twelve tone music of the mid-century musical establishment. For eight years he was unable to compose beyond musical fragments jotted in a notebook. Then, in 1976 a new and radically different voice suddenly emerged with Für Alina, a three minute piece for piano:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

[/unordered_list]

All music flows through time. Listening to the mystical minimalism of Arvo Pärt, there’s an equally powerful sense of time flowing through music. It’s easy to become one with the moment in Pärt’s music. It allows us to “enter inside the sound.” You might be reminded of the meditative, circular flow of Gregorian Chant or the music of Lassus or Palestrina.

Pärt’s style of writing, which suggests the overtones of bells, is known as Tintinnabulation. He describes it here:

Tintinnabulation is an area I sometimes wander into when I am searching for answers – in my life, my music, my work. In my dark hours, I have the certain feeling that everything outside this one thing has no meaning. The complex and many-faceted only confuses me, and I must search for unity. What is it, this one thing, and how do I find my way to it? Traces of this perfect thing appear in many guises – and everything that is unimportant falls away. Tintinnabulation is like this. . . . The three notes of a triad are like bells. And that is why I call it tintinnabulation.

Silentium

Silentium is the second movement of Pärt’s Tabula Rasa (1977):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FK-KC2aQpcI

Here is the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir’s performance of Canon of Repentance, which took place June 2 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.