Beethoven’s great symphonic arc is a study in moderation. Beginning with the Third Symphony (the Eroica), Beethoven’s odd numbered symphonies can be described as heroic, monumental and groundbreaking. By contrast, the even numbered symphonies take a step back into a more intimate world of classical charm.

Beethoven’s great symphonic arc is a study in moderation. Beginning with the Third Symphony (the Eroica), Beethoven’s odd numbered symphonies can be described as heroic, monumental and groundbreaking. By contrast, the even numbered symphonies take a step back into a more intimate world of classical charm.

Listen to Jean Sibelius’ Fifth and Sixth Symphonies back to back, and you’ll hear a similar dichotomy. Sibelius began sketching both works around the same time in the summer and autumn of 1914. The stormy, heroic drama of the Fifth Symphony leads to this transcendent moment in the final movement. The Sixth Symphony, sometimes called the “Cinderella” of Sibelius’ output, is quieter and more desolate. It emerges out of a still, Nordic wood. In its final bars, the fourth movement’s joyful exuberance dissipates, and we’re left where we began…with a gloomy, desolate stillness, as a single lonely pitch fades away. Instead of progressing towards an ultimate goal, the Sixth Symphony explores a beautiful, but static sonic landscape.

“The Sixth Symphony always reminds me of the scent of the first snow,” said Jean Sibelius in 1943. The music is full of shimmering, bright colors as high strings blend with flutes, and occasionally harp. If any music can evoke the clear, blinding brightness of sunlight glinting off of freshly fallen snow, this is it. Out of nordic gloom and a sense of shivering mystery, there are bursts of joy, maybe even giddiness. (this moment in the first movement, for example). But there are also moments of darkness which pop up suddenly, without any warning. At the end of the first movement, we hear a noble proclamation in the horns and then a frightening moment of strange dissonance which grows into a musical thunderclap.

In this transition early in the first movement, listen to the incredible conflict and tension between the strings and tympani. The rising brass chord seems to bring us back where we belong. Late, towards the end of the symphony, listen to the way playful, frolicking music suddenly is overtaken by strange, sustained “wrong” notes in the trumpet.

Most of the Sixth Symphony inhabits the Dorian mode, which sounds like a natural minor scale, until you get to its raised sixth degree. This, in addition to the lowered seventh gives the music a completely different atmosphere from major or minor tonality. In some ways, it looks back to the floating, mediative sounds of Palestrina (1525-1594).

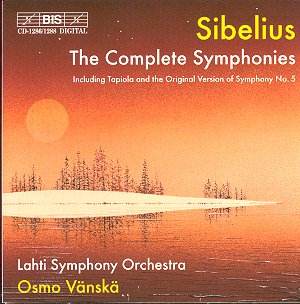

Here is Osmo Vänskä’s recording with the Lahti Symphony Orchestra:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uKhCHvaAc3o

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find Osmo Vänskä’s recording with the Lahti Symphony Orchestra (featured above) at iTunes, Amazon.

- a recording with Leif Segerstam and the Danish National Symphony Orchestra.

- a live performance with Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra.

[/unordered_list]