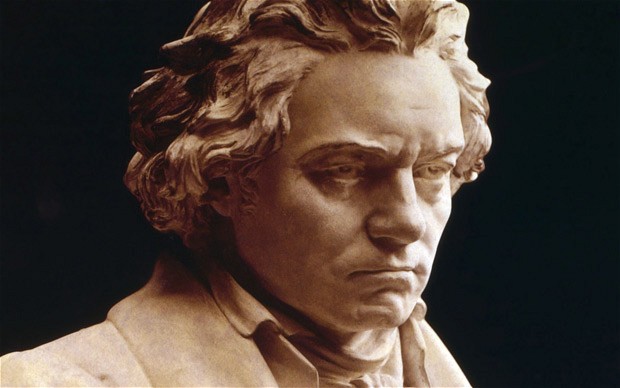

Last week we stepped into the strange, mysterious world of Beethoven’s Late string quartets, music which stylistically leaves behind everything that came before and offers up profound and timeless revelations.

Last week we stepped into the strange, mysterious world of Beethoven’s Late string quartets, music which stylistically leaves behind everything that came before and offers up profound and timeless revelations.

In its own way, Mozart’s last piano concerto (No. 27 in B flat major, KV 595) makes a similar, if more subtle departure. It still sounds like the Mozart we know, but listen carefully and you may notice something different about this music…perhaps an occasional hint of wistful sadness and even wrenching pain.

Concerto No. 27 was first performed in early 1791, the year of Mozart’s death, at a concert that may have marked Mozart’s final public appearance on the concert stage. By this time, Mozart’s performing career was already winding down. His wife, Constanze was ill and he was deeply in debt. He was treated with contempt by the new Emperor, Leopold II. The publisher, Hoffmeister, refused to continue to publish Mozart’s music unless the composer turned out simpler and more popular works, to which Mozart replied, “Then I can make no more by my pen, and I had better starve, and go to destruction at once.” But the sizable amount of music Mozart wrote in 1791 (which included a piece for glass harmonica, a string quartet, the Clarinet Concerto, The Magic Flute, and the Requiem) transcended all of this.

Concerto No. 27 opens with a wordless conversation between two contrasting opera characters. The strings make a quietly passionate opening statement amid playfully comic interjections by the winds. At the 0:37 mark, the final movement of the “Jupiter” Symphony (completed three years earlier in 1788) briefly surfaces. (Listen here for a comparison). Similar to Jupiter, Mozart’s final concerto is filled with counterpoint (multiple musical lines happening at the same time). As you listen, notice all of the musical voices surrounding the piano line: the way they weave together, move apart, and converse. From the violins to the flute, oboe, and bassoon, each voice has a distinct persona and something to say. You can hear this in the passage beginning around 4:00, with the entrance of the flute. Or listen a few moments later when the piano and strings fade into a solitary woodwind line. Notice the way the line grows and changes shape, as the oboe, flute, and piano trade places.

Entering the first movement’s development section, we’re suddenly confronted with one of those hints of sadness I mentioned earlier. This once assured music gradually begins to falter and fade into silent pauses. When the piano enters, we’re in a new and different world. And do you remember those playful woodwind interjections from the movement’s opening? Now they are transformed into a shockingly stern interruption in the wrong key. A moment later, the piano picks up the “interruption” motive and the oboe takes the singing piano melody. Listen for all of this here and then notice the way we return safely home at the recapitulation.

The second movement is a quietly introspective aria. Amid the simple perfection of the opening melody, perhaps a lonely, solemn march, there’s a sense of lingering sadness. Again, notice the way the voices interact: the three distinct voices in the strings, joined by the singing woodwind line in this passage, the oboe joining the bassoon in a single, sustained pitch here, the winds interjecting with a repeated chord a few moments into this excerpt.

The opening melody’s final statement occurs as a shadowy whisper, the piano, flute and violins sharing the melody and creating an almost ghostly sonority. In the final moments of the second movement, there’s a sense that the music doesn’t want to let go as it shifts to a series of deceptive cadences to avoid an ultimate resolution. In the final bars, seven distinct contrapuntal voices can be heard.

The frolicking final movement dances with playful, comic interruptions. The cadenzas in the first and final movements (often improvised by the performer) were written by Mozart. At the end of this final cadenza, the solo piano pauses for a moment of brief introspection. In the final bars, the main motive is tossed around the orchestra as the piano erupts in joyful, bubbling arpeggios.

Nine days after completing Concerto No. 27, Mozart incorporated the final movement’s theme into the song, Sehnsucht nach den Frühlinge:

Come, sweet May, and turn

The trees green again,

And make the little violets

Bloom for me by the brook!

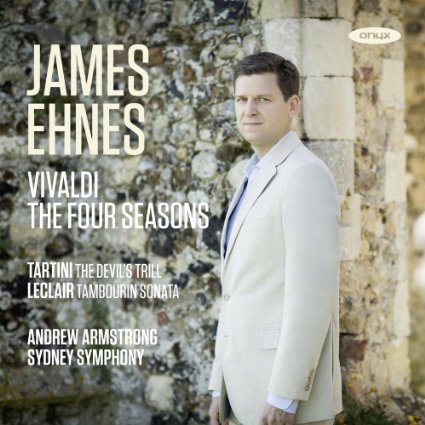

Now that we’ve touched on a few details, let’s listen to the entire piece without interruption. Here is an exceptional performance with Portuguese pianist Maria João Pires and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, conducted by Trevor Pinnock:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c9gvTKdZhD4

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find Maria João Pires’ recording of Mozart’s Concerto No. 27 with Claudio Abbado and Orchestra Mozart at iTunes, Amazon.

[/unordered_list]