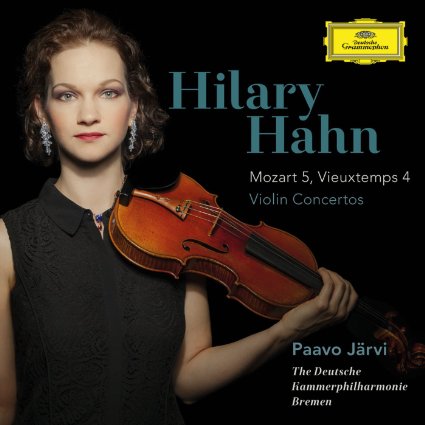

Hilary Hahn released an excellent new recording on March 31. The album pairs Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 5 in A major, K. 219 with the Violin Concerto No. 4 in D minor, Op. 31 by Belgian virtuoso violinist Henri Vieuxtemps (1820-1881). In the recording’s official trailer, Hahn mentions that she first learned both pieces around the age of 10 as she was entering the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. There’s also some interesting violin lineage at work: Hahn’s teacher Jascha Brodsky was a student of Eugène Ysaÿe who studied with Vieuxtemps.

Mozart’s Fifth, written when he was 19 years old, has earned the nickname, “The Turkish Concerto” because of the wild “Turkish” dance in the middle of the final movement. We get hints of this moment of joyful spontaneity in the first movement (1:11 below). These moments stand out on this CD, partly because of the stylish playing of the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, conducted by Paavo Järvi. On older recordings it is common to hear the orchestra in the background and the solo violin prominently front and center. Here, the orchestra is an equal partner, and the balance is similar to what you would hear in a live concert. There’s a great sense of motion and flow in the Adagio.

Here is the first movement:

[unordered_list style=”tick”]

- Find this recording on iTunes

- Find this recording at Amazon

- Find this recording at Deutsche Grammophon

[/unordered_list]

You may notice the influence of Hector Berlioz’ music in the Vieuxtemps. (Amazingly, if you listen closely, you can hear what sounds like birds tweeting on the recording before the music begins). Berlioz said, “Vieuxtemps is as remarkable a composer as he is an incomparable virtuoso.” While this statement may seem exaggerated now, it shows how popular Vieuxtemps’ concertos were in their day. This music still occupies an important place in the violin repertoire. In his book, Great Masters of the Violin, Boris Schwarz says,

Vieuxtemps’ achievement was to rejuvenate the grand concept of the French violin concerto by using the orchestra in a more symphonic manner and by letting the solo violin speak with a more eloquent and impassioned voice. In his Fourth concerto (1849-50) he abandoned the traditional form by inserting a Scherzo and shaping the opening movement freely, almost like an improvisation of the solo violin; there is also a cyclic connection with the Finale.